- a presentation of historical knowledge on the life and times of the Dominican Black Friars in medieval Holbæk and the history of the priory buildings since the Reformation

written by Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig Jakobsen, student at the University of Roskilde (2003)

Who were the Black Friars?

Sortebrødre

is the Danish term for the Black Friars of the Dominican Order, which began in

the early 13th century. The order was established by Dominic (c.1170-1221),

a Spanish canon of the Augustinian Order, after he met with the Catharist

heretics of Southern France. Dominic realised, that the existing orders and the

priests of the secular church could no longer meet with the spiritual needs of

the public. He therefore wanted to start a new community of theologically

learned clerks, who could travel between towns, preaching the gospels and saving

souls, while establishing an apostolic alternative to the Cathars and other

heretics, by living a life of austerity and renunciation of worldly goods. The

order of St Dominic received the blessing of the pope in 1216, allthough it was

only acknowledged as a branch of the Augustinian Order. The official name was Ordo

Praedicatorum, “the

Order of the Preachers” or the Friars Preachers (in Danish prædikebrødre,

“preaching brothers”). Like the other regular orders, who followed the Rule

of St Augustine, the Dominicans did not make a vow of stabilitas loci (to

stay at one place) and should therefore not be termed as monks, but as friars.

They lived in communities in the towns, usually in rather modest buildings,

which officially should not be termed as monasteries, but as priories; still, in

Danish the word for monastery (kloster) is the most common term. Often

the most valuable items of the priory were the books of the Dominican libraries.

The schools of the Dominican Order were mainly concentrated on the education of

preachers, but they could also produce great theological thinkers such as Thomas

Aquinas (c.1225-1274).

Their schools were also open to outside students, such as the parish priests. Possibly,

it was due to this combined training in theology and preaching, that the

Dominican students became skilled debaters and teachers. The new order were

originally directed towards the many kinds of heretics of the High and Late

Middle Ages and the Friars Preachers were put in charge of the Inquisition.

Sortebrødre

is the Danish term for the Black Friars of the Dominican Order, which began in

the early 13th century. The order was established by Dominic (c.1170-1221),

a Spanish canon of the Augustinian Order, after he met with the Catharist

heretics of Southern France. Dominic realised, that the existing orders and the

priests of the secular church could no longer meet with the spiritual needs of

the public. He therefore wanted to start a new community of theologically

learned clerks, who could travel between towns, preaching the gospels and saving

souls, while establishing an apostolic alternative to the Cathars and other

heretics, by living a life of austerity and renunciation of worldly goods. The

order of St Dominic received the blessing of the pope in 1216, allthough it was

only acknowledged as a branch of the Augustinian Order. The official name was Ordo

Praedicatorum, “the

Order of the Preachers” or the Friars Preachers (in Danish prædikebrødre,

“preaching brothers”). Like the other regular orders, who followed the Rule

of St Augustine, the Dominicans did not make a vow of stabilitas loci (to

stay at one place) and should therefore not be termed as monks, but as friars.

They lived in communities in the towns, usually in rather modest buildings,

which officially should not be termed as monasteries, but as priories; still, in

Danish the word for monastery (kloster) is the most common term. Often

the most valuable items of the priory were the books of the Dominican libraries.

The schools of the Dominican Order were mainly concentrated on the education of

preachers, but they could also produce great theological thinkers such as Thomas

Aquinas (c.1225-1274).

Their schools were also open to outside students, such as the parish priests. Possibly,

it was due to this combined training in theology and preaching, that the

Dominican students became skilled debaters and teachers. The new order were

originally directed towards the many kinds of heretics of the High and Late

Middle Ages and the Friars Preachers were put in charge of the Inquisition.

The

Dominican Order soon spread out from Southern France to the whole of Western

Europe. The first friars arrived in Denmark in 1222, where

they

received

the

nickname Black Friars (in Danish sortebrødre, “black brothers”)

because of the colour of the cloak, that they wore on top of the white habit

whenever they served in the church or went outside the priory. At about the same

time, another Mendicant order of St Francis, the Friars Minor - who in Denmark

was to be known as de små brødre (“the small brothers”) or gråbrødre

(“grey brothers”) - also introduced themselves in many European towns. Even

though the two orders had several similarities on the outside, they built on

rather different concepts. The

common term for the brethren of both orders, Mendicants (i.e. “beggars”, in

Danish tiggermunke), refered to the fact that they refused to own

property (individually as well as corporate), and depended upon organised

begging for their support. Among other things, the Mendicant Orders came into

life as a sign of the increasing criticism against the existing orders (especially

the Cistercians, who had Zealand monasteries at Sorø and Esrum), who were said

to be more concerned with collecting and administrating estates, than with

living the apostolic life. The sincere austerity of the friars was therefore a

powerful weapon against the heretics, as the poverty made the brethren both

trustworthy and mobile.

At the same time, however, the Mendicants became dependent on the good

will and generosity of the townspeople, wherever they came.

The

Dominican Order soon spread out from Southern France to the whole of Western

Europe. The first friars arrived in Denmark in 1222, where

they

received

the

nickname Black Friars (in Danish sortebrødre, “black brothers”)

because of the colour of the cloak, that they wore on top of the white habit

whenever they served in the church or went outside the priory. At about the same

time, another Mendicant order of St Francis, the Friars Minor - who in Denmark

was to be known as de små brødre (“the small brothers”) or gråbrødre

(“grey brothers”) - also introduced themselves in many European towns. Even

though the two orders had several similarities on the outside, they built on

rather different concepts. The

common term for the brethren of both orders, Mendicants (i.e. “beggars”, in

Danish tiggermunke), refered to the fact that they refused to own

property (individually as well as corporate), and depended upon organised

begging for their support. Among other things, the Mendicant Orders came into

life as a sign of the increasing criticism against the existing orders (especially

the Cistercians, who had Zealand monasteries at Sorø and Esrum), who were said

to be more concerned with collecting and administrating estates, than with

living the apostolic life. The sincere austerity of the friars was therefore a

powerful weapon against the heretics, as the poverty made the brethren both

trustworthy and mobile.

At the same time, however, the Mendicants became dependent on the good

will and generosity of the townspeople, wherever they came.

The

Mendicant Orders broke from traditional monasticism by abandoning the seclusion

and enclosure of the cloister in order to engage in an active pastoral mission

to the society of their time. The success of the Dominicans built, in a matter

of speaking, on good marketing. They came to the people, where the people was,

and gave to the people, what the people wanted: good preaching (from 1236 even

in the local languages) about how to live the apostolic life of piety and

poverty, which the brethren

themselves were the ultimate example of. The Mendicants also came to the

sick and the poor of the town, to bring them words of comfort and relieving

herbal extracts. To many members of the rich bourgeoisie, the Mendicants

appeared to live as close to the apostolic ideal as humanly possible. The Black

Friars received still more donations and requests for burial places in the

Dominican churches, which many merchant families preferred to the local parish

churches. This of course could create some rivalry with the priests of the

secular church, but there are also many indications of good relations between

the secular priests and the friars. As an example of this is the fact, that the

Dominican schools also were open to the public, which the secular priests

benefited from.

The

Mendicant Orders broke from traditional monasticism by abandoning the seclusion

and enclosure of the cloister in order to engage in an active pastoral mission

to the society of their time. The success of the Dominicans built, in a matter

of speaking, on good marketing. They came to the people, where the people was,

and gave to the people, what the people wanted: good preaching (from 1236 even

in the local languages) about how to live the apostolic life of piety and

poverty, which the brethren

themselves were the ultimate example of. The Mendicants also came to the

sick and the poor of the town, to bring them words of comfort and relieving

herbal extracts. To many members of the rich bourgeoisie, the Mendicants

appeared to live as close to the apostolic ideal as humanly possible. The Black

Friars received still more donations and requests for burial places in the

Dominican churches, which many merchant families preferred to the local parish

churches. This of course could create some rivalry with the priests of the

secular church, but there are also many indications of good relations between

the secular priests and the friars. As an example of this is the fact, that the

Dominican schools also were open to the public, which the secular priests

benefited from.

The

Dominican Order was especially interested in recruiting well-educated youth,

which usually came from the higher urban classes. Also the sons of artisans and

farmers would join the communities, often as lay brothers (conversi), a

lower educated group of the brethren, who took care of the more practical duties

in the priory, but they too worked in the streets and market places with the

preachers. The

friars chosen for preaching spent a lot of their time on their own studying in

the cells of the priory or practising their skills of preaching and

argumentation with the other preachers, all under careful observation by the

elder friars and the lecturer in particular. When the friars were considered

sufficiently educated, they were sent out in the streets (always in pairs) to

help the good people of the town to receive the Gospel and repent their sins.

While offering these services to the lay people, the friars received small

donations of money or goods, which they brought back home to the priory. Another

significant part of the life of the Black Friars (just like any other monastic

order) was the singing of the Divine Office in the priory church at the

canonical hours; 6-7 daily liturgical offices, of which several attracted many

lay visitors, who wanted

to enjoy the graceful singing

of hymns. Besides these daily routines, the Black Friars had to perform still

more requiem masses for the souls of late brethren and lay benefactors of the

community. The services in the church could often become a problem, as it was

never regarded as important for a friar as for a monk. On the other hand, the

celebration of the requiem masses and the Divine Office served a rather

important part of the “public relations” of the Black Friars towards the

people of their town - and the potential benefactors. As

a result, the Dominican Order always tried to make their communities as large as

possible, so that their friars were given more freedom to study or work in the

streets, without the need to worry about the celebrating of the next mass. In

addition, it could be a problem to find good enough lecturers if there were too

many small priories, as every priory was to have its own lecturer. A community

had to consist of at least 12 brethren, as this was the number necessary to

exercise the Divine Office. Besides the actual friars, the community had a

number of lay brothers and novices. The community itself chose the head of the

priory, the prior, among the eldest and wisest of the friars. He was held

responsible for the overall condition of the priory and was to give annual

reports to the provincial chapter of the Dominican Order (in the Nordic province

of Dacia). There were several other important functions in the priory,

such as the gatekeeper, the kitchen master and the gardener. In connection to

many priories, a lodging house (for both travelling Black Friars and lay people)

was allocated and perhaps even a small hospital; at least there was usually one

brother of the community who knew how to treat the most common illnesses and how

to perform the traditional blood-lettings.

The

Dominican Order was especially interested in recruiting well-educated youth,

which usually came from the higher urban classes. Also the sons of artisans and

farmers would join the communities, often as lay brothers (conversi), a

lower educated group of the brethren, who took care of the more practical duties

in the priory, but they too worked in the streets and market places with the

preachers. The

friars chosen for preaching spent a lot of their time on their own studying in

the cells of the priory or practising their skills of preaching and

argumentation with the other preachers, all under careful observation by the

elder friars and the lecturer in particular. When the friars were considered

sufficiently educated, they were sent out in the streets (always in pairs) to

help the good people of the town to receive the Gospel and repent their sins.

While offering these services to the lay people, the friars received small

donations of money or goods, which they brought back home to the priory. Another

significant part of the life of the Black Friars (just like any other monastic

order) was the singing of the Divine Office in the priory church at the

canonical hours; 6-7 daily liturgical offices, of which several attracted many

lay visitors, who wanted

to enjoy the graceful singing

of hymns. Besides these daily routines, the Black Friars had to perform still

more requiem masses for the souls of late brethren and lay benefactors of the

community. The services in the church could often become a problem, as it was

never regarded as important for a friar as for a monk. On the other hand, the

celebration of the requiem masses and the Divine Office served a rather

important part of the “public relations” of the Black Friars towards the

people of their town - and the potential benefactors. As

a result, the Dominican Order always tried to make their communities as large as

possible, so that their friars were given more freedom to study or work in the

streets, without the need to worry about the celebrating of the next mass. In

addition, it could be a problem to find good enough lecturers if there were too

many small priories, as every priory was to have its own lecturer. A community

had to consist of at least 12 brethren, as this was the number necessary to

exercise the Divine Office. Besides the actual friars, the community had a

number of lay brothers and novices. The community itself chose the head of the

priory, the prior, among the eldest and wisest of the friars. He was held

responsible for the overall condition of the priory and was to give annual

reports to the provincial chapter of the Dominican Order (in the Nordic province

of Dacia). There were several other important functions in the priory,

such as the gatekeeper, the kitchen master and the gardener. In connection to

many priories, a lodging house (for both travelling Black Friars and lay people)

was allocated and perhaps even a small hospital; at least there was usually one

brother of the community who knew how to treat the most common illnesses and how

to perform the traditional blood-lettings.

The Dominican priories in Denmark

It is believed that about 20 Dominican priories existed in Denmark in the Middle Ages. Two of these were convents for nuns. They were all terminated during the times of the Reformation and only a few of them have (partially) survived until today. The priory of the Black Friars in Holbæk represents the only remaining buildings of the Dominican Order on the Danish Isles. In three Jutland cities (Viborg, Århus and Ribe), it is still possible to experience the medieval milieu of the Black Friars, in more or less complete priories, also including the Dominican churches.

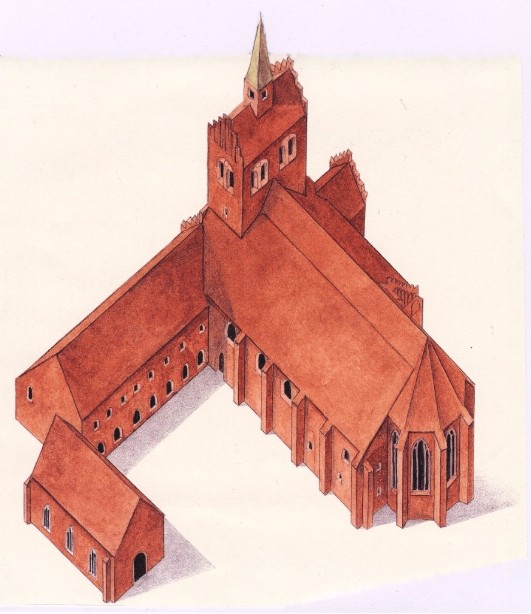

The Priory of the Black Friars in medieval Holbæk

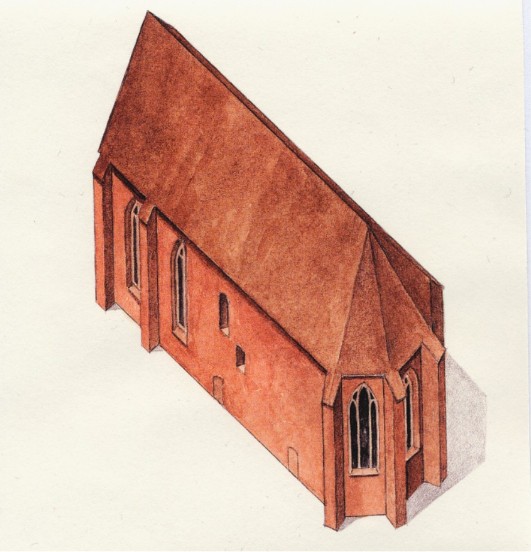

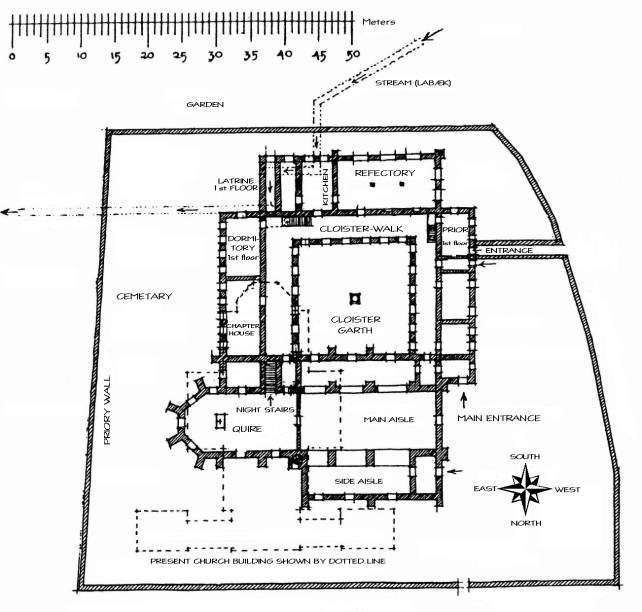

The

Black Friars arrived in Holbæk in 1269 or 1275. Other towns in Zealand with

Dominican priories were Roskilde (1231-34), Vordingborg (1253), Næstved (c.1260s)

and Ellsinore (1441), while a Dominican convent for nuns was founded in Roskilde

in 1263. Also Slagelse may have had a community in the 13th century

before the foundation in Holbæk. The priory in Holbæk was built on a vacant

area south of the medieval town. The friars did not get an easy start in Holbæk,

as a Franciscan chronicle from Roskilde tells us, that in 1287 »the house of

the friars burned down together with the entire city of Holbæk«. In the

early 1290s, the outlawed Marshal Stig and his followers ravaged the town. Finally,

in 1323 Bishop Niels of Børglum could consecrate the church of the Black Friars

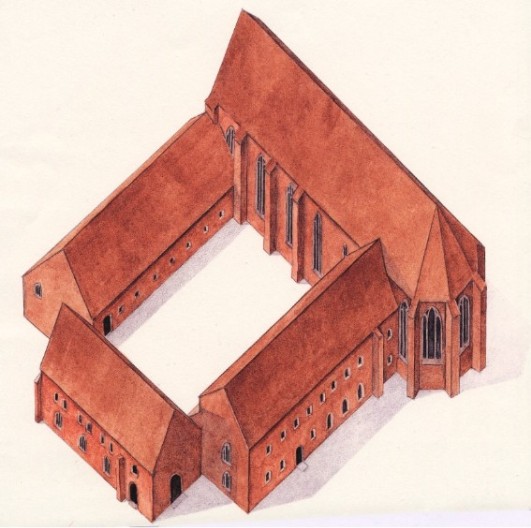

of Holbæk. The church was to become the northern wing of a four-wing priory, as

it was common with both the Dominicans and all other orders. At first, the

church was probably only accompanied by an eastern wing, presumably a two storey

building, where the friars had their daily meeting room (the chapterhouse) on

the ground floor. Other monastic orders would usually have a common dormitory on

the first floor of the eastern wing, but with the

Dominicans,

this was changed into a number of small cells, where the friars could study and

sleep individually. Sometimes a small staircase from the dormitory to the church

quire would ease the brethren’s way to the nightly services of the Divine

Office. Probably, the priory had a number of small rooms for safekeeping of

books. Unfortunately, we know very little about this eastern wing of the priory,

which was demolished just after the Reformation.

The

Black Friars arrived in Holbæk in 1269 or 1275. Other towns in Zealand with

Dominican priories were Roskilde (1231-34), Vordingborg (1253), Næstved (c.1260s)

and Ellsinore (1441), while a Dominican convent for nuns was founded in Roskilde

in 1263. Also Slagelse may have had a community in the 13th century

before the foundation in Holbæk. The priory in Holbæk was built on a vacant

area south of the medieval town. The friars did not get an easy start in Holbæk,

as a Franciscan chronicle from Roskilde tells us, that in 1287 »the house of

the friars burned down together with the entire city of Holbæk«. In the

early 1290s, the outlawed Marshal Stig and his followers ravaged the town. Finally,

in 1323 Bishop Niels of Børglum could consecrate the church of the Black Friars

of Holbæk. The church was to become the northern wing of a four-wing priory, as

it was common with both the Dominicans and all other orders. At first, the

church was probably only accompanied by an eastern wing, presumably a two storey

building, where the friars had their daily meeting room (the chapterhouse) on

the ground floor. Other monastic orders would usually have a common dormitory on

the first floor of the eastern wing, but with the

Dominicans,

this was changed into a number of small cells, where the friars could study and

sleep individually. Sometimes a small staircase from the dormitory to the church

quire would ease the brethren’s way to the nightly services of the Divine

Office. Probably, the priory had a number of small rooms for safekeeping of

books. Unfortunately, we know very little about this eastern wing of the priory,

which was demolished just after the Reformation.

The

oldest still existing part of the Dominican priory in Holbæk is the southern

wing, which can be dated to the early or middle 15th century. This

wing too was built in two storeys, with an arched ceiling and a cellar. The

original cellar still exists, while the arches have been reconstructed. This

building most likely contained the kitchen and the dining hall (refectorium)

of the priory,

which might even have had the pleasures of “running water”. Possibly,

a small stream was led through the eastern part of the wing, for the benefit of

the kitchen, a washroom and a latrine (in that respectable order); many of the

medieval monks and friars had rather sophisticated knowledge of hydraulics.

Together with the eastern wing, the eastern part of the southern wing was

demolished after the Reformation. The dining hall, on the other hand, is

expected to have been quite similar to the still existing “klostersal”

(priory hall).

The

oldest still existing part of the Dominican priory in Holbæk is the southern

wing, which can be dated to the early or middle 15th century. This

wing too was built in two storeys, with an arched ceiling and a cellar. The

original cellar still exists, while the arches have been reconstructed. This

building most likely contained the kitchen and the dining hall (refectorium)

of the priory,

which might even have had the pleasures of “running water”. Possibly,

a small stream was led through the eastern part of the wing, for the benefit of

the kitchen, a washroom and a latrine (in that respectable order); many of the

medieval monks and friars had rather sophisticated knowledge of hydraulics.

Together with the eastern wing, the eastern part of the southern wing was

demolished after the Reformation. The dining hall, on the other hand, is

expected to have been quite similar to the still existing “klostersal”

(priory hall).

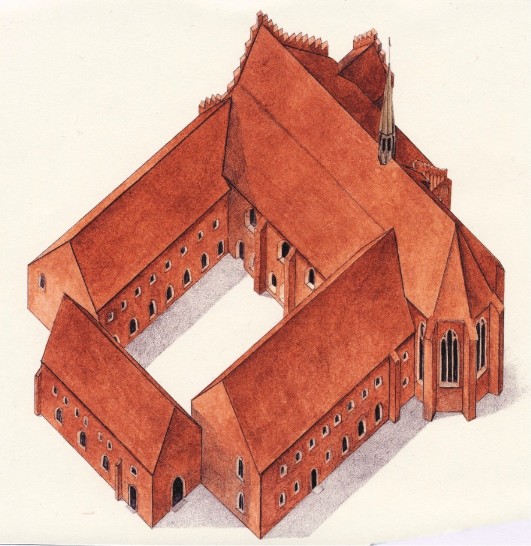

The

youngest part of the priory is the western wing, which has been dated to the

early 16th century. It is possible, however, that the priory also in

earlier

times

formed a closed group of buildings, as the present western wing might have

replaced an earlier and simpler wing or a wall. This too was a two-storey

building, built in red stones as the rest of the priory, with an arched ceiling

on the ground floor. In both the southern and the western wing, the arches have

been decorated with frescos. There

do not seem to be any strict regularity as to what the western wing of a

Dominican priory was used for, but many priories are known to have used them for

libraries and schools, a tendency especially significant in the late Middle

Ages. In Holbæk, we also have reason to believe that both the prior and the

gatekeeper had their rooms in this wing. On the eastern side of the west

wing, directed into the cloister, remnants of a covered cloister-walk have been

found. A wall was surrounding the entire priory and remnants of this can still

be seen to the southeast of the church. On the inside of the wall, to the east

of the long gone eastern wing, was the cemetery of the priory. To the south of

the buildings was the garden of the brethren.

The

youngest part of the priory is the western wing, which has been dated to the

early 16th century. It is possible, however, that the priory also in

earlier

times

formed a closed group of buildings, as the present western wing might have

replaced an earlier and simpler wing or a wall. This too was a two-storey

building, built in red stones as the rest of the priory, with an arched ceiling

on the ground floor. In both the southern and the western wing, the arches have

been decorated with frescos. There

do not seem to be any strict regularity as to what the western wing of a

Dominican priory was used for, but many priories are known to have used them for

libraries and schools, a tendency especially significant in the late Middle

Ages. In Holbæk, we also have reason to believe that both the prior and the

gatekeeper had their rooms in this wing. On the eastern side of the west

wing, directed into the cloister, remnants of a covered cloister-walk have been

found. A wall was surrounding the entire priory and remnants of this can still

be seen to the southeast of the church. On the inside of the wall, to the east

of the long gone eastern wing, was the cemetery of the priory. To the south of

the buildings was the garden of the brethren.

Just

as in the rest of the European cities, the Black Friars seem to have been quite

popular in Holbæk for a long period. Among other things, the several extensions

and additions to the church and the rest of the priory indicate this. Such

building projects must have been quite expensive and according to the rules of

the order, they could only be financed by gifts from people outside the order.

One of the more generous contributions, which is known to have financed a major

extension to the church in 1456, came from Queen Dorothea. Actually, it seems as

if most of the major building projects were based on royal support. But if such

extensions were to have any meaning at all, they must be seen as signs of a

growing interest among the local citizens for the priory church and perhaps even

by young men of Holbæk to join the community.

Just

as in the rest of the European cities, the Black Friars seem to have been quite

popular in Holbæk for a long period. Among other things, the several extensions

and additions to the church and the rest of the priory indicate this. Such

building projects must have been quite expensive and according to the rules of

the order, they could only be financed by gifts from people outside the order.

One of the more generous contributions, which is known to have financed a major

extension to the church in 1456, came from Queen Dorothea. Actually, it seems as

if most of the major building projects were based on royal support. But if such

extensions were to have any meaning at all, they must be seen as signs of a

growing interest among the local citizens for the priory church and perhaps even

by young men of Holbæk to join the community.

In

the early 16th century, the Mendicant Orders especially suffered in

the clash between the reformists and the orthodox Catholic Church. Reformed

secular clerks managed to turn the public opinion against the friars of all

orders in the Danish cities. Also, the Black Friars of Holbæk must have feared

some sort of infringement, as they obtained a letter of protection from Count

Christopher of Oldenburg during a Danish civil war 1533-1536, known as Grevens

Fejde (“The Feud of the Count”). February 1535, however, the friars

themselves gave up their presence in Holbæk and the priory was given to the

citizens of Holbæk, as a place for the sick and the poor. More than physical

abuse, the friars of Holbæk seem to have given up because of a lack of economic

support from the surrounding society, which was so vital for their existence. We

do not know whereto the Black Friars of Holbæk went, but the order of St

Dominic continued to work in the Roman Catholic countries of Southern Europe.

From other Danish towns, we even have examples of former Mendicant friars who

became reformed parish vicars.

In

the early 16th century, the Mendicant Orders especially suffered in

the clash between the reformists and the orthodox Catholic Church. Reformed

secular clerks managed to turn the public opinion against the friars of all

orders in the Danish cities. Also, the Black Friars of Holbæk must have feared

some sort of infringement, as they obtained a letter of protection from Count

Christopher of Oldenburg during a Danish civil war 1533-1536, known as Grevens

Fejde (“The Feud of the Count”). February 1535, however, the friars

themselves gave up their presence in Holbæk and the priory was given to the

citizens of Holbæk, as a place for the sick and the poor. More than physical

abuse, the friars of Holbæk seem to have given up because of a lack of economic

support from the surrounding society, which was so vital for their existence. We

do not know whereto the Black Friars of Holbæk went, but the order of St

Dominic continued to work in the Roman Catholic countries of Southern Europe.

From other Danish towns, we even have examples of former Mendicant friars who

became reformed parish vicars.

The priory since the Reformation

The

citizens of Holbæk soon decided to turn the grand Dominican church into a

parish church. For the rest of the buildings, King Christian III did not pay

much attention to the wish of the friars, about using the abandoned priory for

the benefit of the poor. In 1536, he gave the orders to tear down the domestic

buildings of the priory and let the stones be used for improvements on Holbæk

Castle. Evidently, the citizens must have succeeded in changing his mind, even

though it appears to have been a little late: The eastern wing and perhaps also

the eastern part of the southern wing were already demolished. The remaining

buildings of the Black Friars were hereafter in the hands of the city. The

western wing became a grammar school for the privileged youth, while the

southern wing was turned into a city hall. An elevated first floor in the

western end of this wing was used as jail and was for this reason known as the

“Prison Tower”.

The

citizens of Holbæk soon decided to turn the grand Dominican church into a

parish church. For the rest of the buildings, King Christian III did not pay

much attention to the wish of the friars, about using the abandoned priory for

the benefit of the poor. In 1536, he gave the orders to tear down the domestic

buildings of the priory and let the stones be used for improvements on Holbæk

Castle. Evidently, the citizens must have succeeded in changing his mind, even

though it appears to have been a little late: The eastern wing and perhaps also

the eastern part of the southern wing were already demolished. The remaining

buildings of the Black Friars were hereafter in the hands of the city. The

western wing became a grammar school for the privileged youth, while the

southern wing was turned into a city hall. An elevated first floor in the

western end of this wing was used as jail and was for this reason known as the

“Prison Tower”.

The

grammar school was closed in 1739 during a major educational reform in Denmark.

Hereafter, the “Latin School” became a “Danish (elementary) School” for

the children of all social classes. In 1902, the school was moved to another

site and the western wing of the priory became residence for the new public

library. For a period in the 1910s, the city museum used the rooms of the ground

floor. In 1922, the interior of the western wing underwent a major rebuilding.

For the southern

wing, the time as city hall continued to 1844. Then came a period of 20 years,

where the pious will of the long gone friars

was actually followed:

the southern building became a home for the poor and was used as a

hospital during the cholera epidemics in the middle of the 19th

century. This ended in 1863, where the southern wing was rebuilt into its

present exterior form and the medieval refectory was turned into a mortuary. The

original arches of the refectory hall had been torn down in 1783, along with the

“Prison Tower”, but in 1916, six new arches replaced the flat plaster

ceiling of the mortuary. Unfortunately, the medieval convent church does not

exist anymore, as it was torn down in 1869 to be replaced by a more modern

building. While the new church was built in 1869-1872, the hall of the southern

wing (in Danish known as Klostersalen) served as a temporary

church room. The two tombstones in the eastern wall of the hall were originally

placed in the old church. The one to the left commemorates a commander of Holbæk

Castle, Christoffer von Festenberg Pax (†1608),

together with his wife and children, while the stone on the right pictures a

local vicar and a curate from the early 17th century.

The

grammar school was closed in 1739 during a major educational reform in Denmark.

Hereafter, the “Latin School” became a “Danish (elementary) School” for

the children of all social classes. In 1902, the school was moved to another

site and the western wing of the priory became residence for the new public

library. For a period in the 1910s, the city museum used the rooms of the ground

floor. In 1922, the interior of the western wing underwent a major rebuilding.

For the southern

wing, the time as city hall continued to 1844. Then came a period of 20 years,

where the pious will of the long gone friars

was actually followed:

the southern building became a home for the poor and was used as a

hospital during the cholera epidemics in the middle of the 19th

century. This ended in 1863, where the southern wing was rebuilt into its

present exterior form and the medieval refectory was turned into a mortuary. The

original arches of the refectory hall had been torn down in 1783, along with the

“Prison Tower”, but in 1916, six new arches replaced the flat plaster

ceiling of the mortuary. Unfortunately, the medieval convent church does not

exist anymore, as it was torn down in 1869 to be replaced by a more modern

building. While the new church was built in 1869-1872, the hall of the southern

wing (in Danish known as Klostersalen) served as a temporary

church room. The two tombstones in the eastern wall of the hall were originally

placed in the old church. The one to the left commemorates a commander of Holbæk

Castle, Christoffer von Festenberg Pax (†1608),

together with his wife and children, while the stone on the right pictures a

local vicar and a curate from the early 17th century.

In

1959, the library moved out of the western wing and later the mortuary was

transferred to the new cemetery in the eastern part of town. The old Dominican

buildings were once again restored in the 1970s, and the premises were converted

into offices for the parish administration and meeting facilities for the Church

of St Nicholas (Skt. Nikolai Kirke). One could say, that the parish clerk

has returned to the old priory after a century, as the clerk actually had his

private residence in the buildings back in the 1870s, along with a small garden

south of the priory, where also the medieval friars had grown their vegetables

and herbs. Today, however, the parish clerk only resides here during office

hours. The latest restoration was meant to recreate the original appearance of

the priory as much as possible. This aim did not only include the actual

buildings, but also the entire environment around the premises, where the

grounds should offer a peaceful place in the middle of town.

In

1959, the library moved out of the western wing and later the mortuary was

transferred to the new cemetery in the eastern part of town. The old Dominican

buildings were once again restored in the 1970s, and the premises were converted

into offices for the parish administration and meeting facilities for the Church

of St Nicholas (Skt. Nikolai Kirke). One could say, that the parish clerk

has returned to the old priory after a century, as the clerk actually had his

private residence in the buildings back in the 1870s, along with a small garden

south of the priory, where also the medieval friars had grown their vegetables

and herbs. Today, however, the parish clerk only resides here during office

hours. The latest restoration was meant to recreate the original appearance of

the priory as much as possible. This aim did not only include the actual

buildings, but also the entire environment around the premises, where the

grounds should offer a peaceful place in the middle of town.