Agriculture and Settlement

in Medieval and Early Modern Zealand

A historical-geographical survey of Danish agriculture

and settlement conditions, c.1000-1688

Master’s

thesis by Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig Jakobsen

Institute of Geography

Roskilde

University 2004

Supervisor:

Jesper Brandt

Abbreviated

edition in English 2005

Introduction and summary

This is an

abbreviated edition in English of my master’s thesis presented to and approved by

the Institute of Geography at Roskilde University in the summer of 2004.

The main

goal of the present master’s thesis is to produce new knowledge on the

development of agriculture and settlement structure in Denmark during the

period c.1000-1688. Studies of historical geography in Denmark earlier

than 1688 are traditionally based upon retrospective use of the national Land

Register of 1688. In my paper, I try to show that such retrospective studies

for an average Danish region can be supplemented by several earlier sources of

various kind, which used with an understanding of the nature of the data and

their problems, actually can contribute intensively to our understanding of the

agricultural and settlement conditions in medieval Denmark. A basic part of my

report is therefore to present the potential data sources and evaluate their

usefulness for historical-geographical studies, including a presentation of old

and new methods to analyse the data. My historical sources can be grouped in

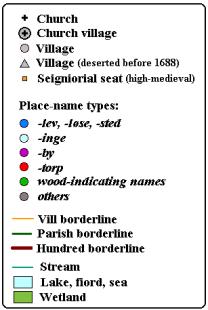

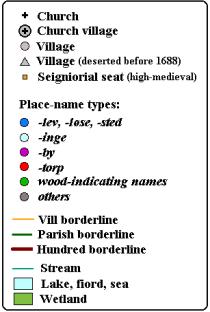

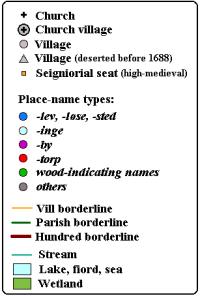

four classes. 1. Place-name types of the settlements; 2. Written economical

registers of parishes or villages; 3. Church buildings; 4. Structures of

parishes and village land units (vills). The presented data sources and methods

have been tested on a case study area of NW-Zealand, where it has been my aim

to describe the demographical, economical and agricultural situation at

different times in the period. In the analyses, the mentioned data has also

been compared to the natural-geographical conditions of the studied region. For

this purpose, I have pointed out twelve land-type areas with different but

representative soil and terrain types.

The

analyses begin with the land registers of the seventeenth century, where I have

combined the data of the two registers (1662 and 1688) with the reconstructed

areas of the vills (ejerlav) to calculate various relations, analyse the

regional distribution of these relations and evaluate their differences between

the twelve chosen land-type areas. By doing this, it has been possible to identify

areas of different degrees of cultivation, seed density, crop mix, orientation

of production (cattle versus grain), and land value. In the following chapters,

I have tested earlier sources such as place-name distribution, size of the

church buildings, parish structure and settlement pattern within the parishes,

and a set of taxations recorded in the Roll of the Bishop of Roskilde (c.1300).

In my

analyses, I have looked with special interest on the ‘thorpe-foundation’, that

is the foundation of a vast number of new settlements mainly dated to the high

medieval period, primarily with the place-name suffix -thorp, but in

this study also with other suffixes such as -tved and -rød. It is

quite clear, that in NW-Zealand the term thorpe has both been used on hamlets

founded close to the old villages (adelbyer) on their land, and on new

settlements in hitherto uncultivated wasteland. Also, it is possible to follow,

how some districts developed more thorpes than others. Differences in soil and

terrain, and related differences in production, can explain some of the

variations, but as areas with apparently similar conditions would end up with

quite different numbers of thorpes, also the aspect of time and perhaps

lordship has been suggested as possible influences. Especially in the

woodlands, some thorpes have been deserted in the Late Middle Ages, but it has

been quite difficult to find any signs of a general ‘Late Medieval Crisis’. On

the contrary, several areas within the region show signs of economical and demographical

growth during this latter part of the studied period.

Related to

this, I have tried to find any correlation between settlement structure and

agricultural production on the one side, and natural conditions such as soil

types and terrain on the other - also in order to see, if it is possible to

identify a general change in the perception of land value. From beginning to

end, it was the soils formed on moraine clay that held the highest evaluation,

with only small internal variations regarding the exact texture (light, medium

or heavy clay). Much more secondary was land (of all soil types) in hilly

terrain, and land dominated by sandy soils or wetland. It seems, however, as if

all the ‘secondary land types’ increased in relative value during the Late

Middle Ages and early Modern Ages, which can be explained by an increased

importance of both rye (sandy soils) and cattle (wetlands), and more clearing

of forest (hilly terrain).

Contents:

1. Tradition of historical geography in Southern Scandinavia

2. Presentation of the studied region : North-Western Zealand

3. Agriculture in seventeenth-century NW-Zealand

4. Settlement in medieval and early modern NW-Zealand

5. Churches and parish structures in medieval NW-Zealand

6. Medieval economy in NW-Zealand : ‘Episcopal taxation’

1.

Tradition of historical geography in Southern Scandinavia

The study

of historical geography in Europe regarding medieval agriculture and settlement

structure has often taken quite different forms reflecting the source situation

of each country. In Scandinavia, extant written material from the High Middle

Ages is rather scarce. This is especially evident on matters concerning

historical geography. Therefore, alternative methods have been developed to an

extent that might put us ahead of countries blessed with a richer textual

tradition. In the historical-geographical area, archaeology and place-name

studies can be pointed to as ‘Scandinavian specialities’.

But also on

a Scandinavian level, the medieval source situation differs among the countries,

resulting in different orientations of the national schools. The scarcity of

written material is, for instance, more distinct in Sweden than it is in

Denmark, but then the Swedes are in possession of an enviable amount of

numerous and detailed cadastral maps from the seventeenth century, where the

oldest mapping of Denmark of a similar quality is about 100 to 150 years later.

Logically, this has resulted in a historical-geographical tradition in Sweden

based upon the use of these maps, which for medieval studies have found use in

a retrospective way. However, it is also possible to identify a more general

tendency in Swedish historical geography towards a ‘cartographical thinking’

than what you will find in Denmark. Studies of medieval church building can be

used as an example. In Denmark, most of the medieval churches are preserved,

usually without any major exterior changes since the late sixteenth century.

Danish church-historical scholars have therefore based their studies and

theories on the physical church buildings and the variations of these, which

combined with sociohistorical speculations has led to a lasting dispute on the

question: Who built the churches - landlords or (groups of) peasants? In

Sweden, the number of preserved medieval churches is considerable smaller than

in Denmark, so instead, scholars here - traditionally based in cartography -

have looked into parish structures and their possible developing. Of course,

both questions have also been taken up by scholars in the respective neighbouring

countries, but never with same intensity, and often with a twist towards their

own ‘national school’: In Denmark, the physical size and shape of the churches

have been used to determine their place in the parish formation; in Sweden, the

seventeenth-century cadastral maps are used to determine whether churches were

built on demesnes land or common village land. Just as a number of Swedish

retrospective-medieval studies are based on cadastral maps of the seventeenth

century, retrospective studies of Danish medieval geography and society are

traditionally based on seventeenth-century Land Registers (see chapter 3).

The

starting point of historical-geographical tradition in Denmark was the study of

place-names, where linguistic elements in settlement names according to

place-name scholars can be dated to different periods. Some of the pioneers in

place-name-based historical geography in Denmark are Johannes Steenstrup

(1894-95) and H.V. Clausen (1916), who were able to identify systematic

differences in size (both physical and economical) and geographical

distribution of villages with different place-name suffixes. This was used to

advance theories on differences in age and reason for foundation of settlements

with different name-types, and ever since, place-name material has been a

traditional part of Danish settlement studies concerning Iron Age, Viking Age,

and the Middle Ages (the principles are used in this survey in chapter 4).

Another

important aspect in early South Scandinavian settlement-historical geography

has been the strikingly regulated ground-plan of many villages and fields, as

they are known from late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century cadastral

maps (Lauridsen 1896). The original inspiration came of course from people

abroad like August Meitzen, but in Sweden and Denmark it was soon argued that

village- and field structures depicted on early modern maps probably could not

be attributed further back than the late High Middle Ages (Larsen 1918,

Lindgren 1939). Indeed, several studies have indicated an extensive settlement

reform in the fourteenth century. The physical structure of villages also

became the main focus of one of the leading historical geographers of Denmark,

Frits Hastrup (1964), who classified all Danish villages by their form and

internal structure, and based on this he propounded the thesis that medieval

villages were subjects to a most consistent spatial regulation, as the breadth

of the toft (that enclosed the individual farm within the village site) quite

accurately should reflect the farm’s share of the village field, and thereby

also its basis of assessment.

Next to

place-name studies, archaeology has made up one of the most important

cornerstones in South Scandinavian settlement-geographical history, as

archaeology at a very early time (mid-nineteenth century) was commonly

integrated with other disciplines related to landscape and settlement studies,

such as history, human geography, and physical geography. Among Danish pioneers

was archaeologist Sophus Müller (1904), who studied the connection between

ancient road systems, landscape topography, and burial mounds. The works and

ideas of Müller were continued by Vilhelm la Cour (1927) and Therkel Mathiassen

(e.g. 1959) with studies in a large regional scale, while Gudmund Hatt (e.g.

1938) performed an impressive series of thorough point-studies. All of them

agreed that settlement-historical development derived from natural conditions

in the physical geography, and - closely related to this - from agronomics. In

recent years, point-studies have dominated Danish settlement archaeology of

which the most famous example is the excavation of the Jutland village Vorbasse

(Hvass 1984), where it has been established, how the actual site of the

settlement has moved several times within a limited area up through the Iron

Age to the early High Middle Ages. In the 1970s, Erland Porsmose (1977, 1979)

and Torben Grøngaard Jeppesen (1979) conducted a series of settlement-historical

studies of villages on the island of Funen, in which archaeology took a leading

rôle. The Funen project supported the picture from Vorbasse of a break in

settlement continuity around the transition from Viking Age to early High

Middle Ages (i.e. 1000-1100).

The

agricultural side of Danish medieval-historical geography was at an early stage

taken up in a broad, synthesizing form by historians Kristian Erslev (1898),

Erik Arup (1925), and Aksel E. Christensen (1938), after which the discipline

was characterized by the publication of several extensive and informative

sources. A such with great importance for subsequent Danish studies in

historical settlement and agriculture is a collection of tables edited by

Henrik Pedersen (1928), presenting the main economical data of the Land

Register of 1688 (on the level of vills, parishes, and hundreds); both the

source and the data is further described (and used) in chapter 3. Among the

most important Danish medieval source publications is the Roll of King

Valdemar II (mid-thirteenth century), which was published, translated, and

extensively commentated by Svend Aakjær in three comprehensive volumes in

1926-43. Among other things, the roll contains a unique and most informative

taxation list for the villages on the island of Falster (situated south of

Zealand) c.1250-60. For the studies of medieval-historical geography on

Zealand, a highly valuable source is the Roll of the Bishop of Roskilde

(c.1370), published in 1956 by C.A. Christensen; the source is presented

and used in this survey’s chapter 6. Furthermore, a number of various less

extensive rolls and registers from the mid- and late-sixteenth centuries, not

least from Zealand, have been published, but perhaps due to their more regional

character, they have never received the same attention as the three

first-mentioned. The named publishers were, by the way, also the leading

scholars of contemporary agricultural-historical studies and debate in Denmark.

The

regional perspective in historical geography was quite early introduced in

Southern Scandinavia, especially among Scanian scholars (: Scania is the

southernmost part of Sweden, and was until 1658 a part of Denmark; both as a

Danish and a Swedish province, Scania has always held a special, regional

identity). Based on material from the eighteenth century, Åke Campbell (1928)

divided the province into three cultural-geographical types of regions called bygder:

plain-bygd (characterized by nucleated villages, open-field systems, and arable

production); wood-bygd (small, dispersed settlements, mainly based on pastural

production); and coppice-bygder (a combination of the two former types). In

1942, this was followed up and improved by a now classical doctor’s thesis of

Sven Dahl on settlement conditions and historical agronomics in Scania from the

sixteenth to the nineteenth century, in which he also included

natural-geographical conditions. Regional geography has a long and strong

tradition in Sweden, where among others Gunnar Lindgren (1939) at an early

point founded a school with his agricultural-historical studies of Falbygden in

Western Götaland. After World War II, the interest for regional-historical

geography also reached Denmark, e.g. with the studies by Ole Widding (1948) of

different types of field-systems on the island of Lolland. Local-scaled studies

of great regional value were performed by Carl Rise Hansen and Axel Steensberg

of field-systems in several Zealand villages (e.g. Hansen & Steensberg

1951, Steensberg 1968, 1974).

In the

second half of the twentieth century, Danish historical geography has produced

several thematical works on various topics within the discipline. Poul Meyer

(1949) gave a thorough account for historical settlement and agricultural

conditions, as these are reflected in preserved rules from old Danish village

regulations. A legal-historical perspective, which Annette Hoff (1997) has

followed up on with a fruitful use of Danish medieval law material. Erik Ulsig

(1968) has given a detailed account for medieval property structures, especially

on Zealand, a theme which in these years have been - and still are - object of

great attention among Danish scholars; an example of this is Carsten Porskrog

Rasmussen’s (2003) work on types of manorial structures in early modern

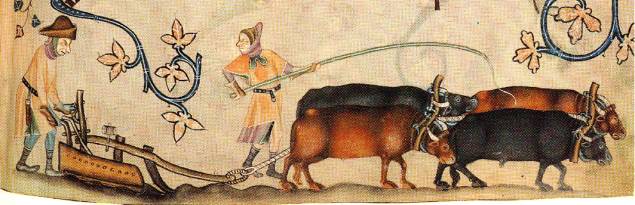

Schleswig. A more technical theme has been exhaustively tested and analysed by

Gritt Lerche (1994), and thereby generated remarkable new knowledge on

development and usage of the plough from ancient times till today. Another

thematical expert in recent historical geography in Denmark is Bo Fritzbøger

(e.g. 1992), who has specialized in forest history.

The vast of

majority of the scholars mentioned above are historians. The ‘grand ole men’

among geographers in Danish historical geography are the already mentioned

Frits Hastrup together with Viggo Hansen. Hansen (1964) conducted a regional

analysis of the connection between the development of settlement structure

(mainly based on place-name material) and natural conditions in Vendsyssel,

Northern Jutland. Scholarly attention was especially given to his including of

physical distance as an explanatory parameter in settlement geography, both

locally and for the structure of the individual vill. In consonance with old

masters like Ricardo and von Thünen, Hansen (1977) pointed to distance between

place of production and place of sale as a most influential factor in the

growing market economy of the Middle Ages. Inspired by Michael Chisholm (1962)

in England, Hansen (1973) too claimed he could find evidence in Denmark for the

thesis that the strips of village-field closest to the settlement site

generally were higher assessed than others, which he explained by a more

intensive tillage of the inner field area in form of manuring, marling, summer

ploughing, etc. Based on these studies and theses, he estimated a

general boundary between the intensively cultivated infield and the more

extensively used outfield to set in at about 800-1000 metres from the village

site. In a sense, these two leaders of historical geography within Danish

geography did each represent one of the two schools of the contemporary shift

in international historical geography: while Frits Hastrup employed a rather

static-retrospective view and method in his settlement-structural studies,

Viggo Hansen’s ideas and interpretations were highly based on the new thoughts

in historical geography of constant dynamics. Whereas Hansen therefore perhaps

is to be considered the most progressive of the two, Hastrup succeeded in

creating the settings for an actual historical-geographical environment at

Århus University during the 1970s together with American Robert M. Newcomb

(1970, 1975, 1979), where the latter among other things should be credited for

his work for the introduction of new methods and statistical tests in Danish

historical geography.

In post-war

Sweden as a whole (i.e. besides the province of Scania), the leading

personality in historical geography was David Hannerberg (e.g. 1955, 1971), who

developed a series of metrological methods for the study of past settlements

and agriculture on a micro level, something which was to have a huge impact on

future orientation in Swedish historical geography. Historical geography in

Sweden also became quite inspired by the new ‘topographical-genetic’ school of

German historical geography with its Siedlungsarchäologie, and during the 1950-60s emerged a strong

Swedish tradition for interdisciplinary projects between archaeology and

geography, especially in Stockholm and Lund, involving geographers like Sölve

Göransson and Staffan Helmfrid (1962). At first, the interdisciplinarity was

mainly individual, and so a matter of one person involving several disciplines

in his or her analyses. One of the first examples of interdisciplinary

historical geography in Southern Scandinavia involving two or more scholars

from different disciplines was implemented in Eastern Götaland in the 1960s,

and from the mid-1970s, this idea has been followed up by several major

interdisciplinary projects. The perhaps most famous and ambitious of these is

the Scanian Ystad Project, commenced in 1979 as a joined project among

three faculties at Lund University. The Ystad Project has generated a series of

publications since the late 1980s, with a main publication in 1991 (Berglund

1991), where a row of both experienced and young scholars based on extensive

studies have succeeded in giving a detailed, broad covering, and synthesizing

presentation of the historical-geographical development in Southern Scania from

the stone age till modern times. In the same period, Danish scholars were

involved in the big Pan-Scandinavian Ødegårdsprojekt, with focus on

traces and consequences in Scandinavian settlement structure of the - at that

time highly debated - ‘Late Medieval Crisis’. In Denmark, the project resulted

in two very informative and inspiring surveys from Hornsherred in Zealand

(Gissel 1977) and the island Falster (Gissel 1989), which both - in spite of

the name and original idea of the overall project - go far beyond just dealing

with derelict farms.

Altogether,

the 1970s classify as the grand decennium of historical geography in Southern

Scandinavia. The discipline has never since held a similarly visible rôle in

Danish research and education of students, where the historical-geographical

tradition for the last generation has been carried on by individuals. As

leading Danish personalities of the discipline in recent years, Erland Porsmose

and Karl-Erik Frandsen stand out. Through a long series of publications, the

archaeologically trained historian Erland Porsmose (e.g. 1977, 1979, 1981,

1987, 1988) has presented an exhaustive overall analysis of settlement and

agricultural development on the island of Funen from the Viking Age to the

seventeenth century, which can be considered the backbone of today’s knowledge

and understanding on rural Denmark in this period. In 1983-84, Karl-Erik

Frandsen (historian and geographer) performed two ‘neo-classical’ atlases on

the distribution of various types of field-systems in seventeenth-century

Denmark, and retrogressive mappings of regional settlement structures, with the

exact vill- and parish organization for the entire country in 1682-83 and c.1820.

Today, it

is fair to speak of a growing renaissance for historical geography in Denmark,

even though the term itself is rarely used. Several scholars from all of the

potentially related disciplines have for the last 10-15 years generated an

extensive amount of transdisciplinary studies within the

historical-geographical boundaries. An attemptive status of current

Danish historical geography - which far from claims to be complete - could be

listed up as follows. One of the few scholars in Denmark, who actually terms

himself a ‘historical geographer’, is human geographer Jørgen Rydén Rømer (e.g.

1976, 2000), who has performed a number of thorough analyses of agricultural

and settlement conditions in Jutland in the 1680s, while historical geography

of the Faroe Islands is almost synonymous with geographer Rolf Guttesen (e.g.

1992, 1996, 2004). Also, several geologists have recently joined the

interdisciplinary field, such as Niels Schrøder (2004), Kristian Dalsgaard

(e.g. 1984, 2001), and Mogens Greve (2000); the latter by developing a

G.I.S.-model for identifying hidden settlement sites from soil data and a

taxation list from 1844. Obvious interdisciplinary partners for the geologists

are the archaeologists, where especially Jens Andresen (e.g. 2004), Charlotte

Fabech and Jytte Ringtved (2002) have shown great interest in working with

scholars, methods, and data from other disciplines. One archaeologist, Helge

Nielsen (1979, 2002), even has left the trowel in favour of digging into the

written sources of medieval agronomics.

In Denmark,

the interdisciplinary field of historical geography has traditionally enjoyed

many fruitful visits from historians, and fortunately, this is still the case.

Fine examples of this are the agricultural and economical-historical studies of

especially Southern Jutland performed by Bjørn Poulsen (e.g. 1997, 2003, 2004),

and Per Grau Møller’s studies of extant relicts of medieval high-backed ridges

(1995) and the development of settlement in different types of landscapes on

Funen (2000). In the latest years, tireless Erik Ulsig (2001, 2004) has

continued his exhaustive studies of the correlation of late medieval plague and

agricultural crisis on the one side with contemporary changes in size of

population and land prices on the other. Peter Korsgaard has not only performed

interesting analyses based on historical maps on his own (e.g. 1988, 1995), he

has also put a great effort in teaching others about the possibilities - and

pitfalls - of working with old maps in historical geography (e.g. 2004).

Finally, church archaeologists Ebbe Nyborg (1979, 1986) and Jes Wienberg (1993)

have compared medieval church building with contemporary demography, economy,

and sociohistorical conditions.

Scanian

tradition for historical geography has in recent years been continued by human

geographer Mats Riddersporre (e.g. 1995) and his studies of the province’s historical

settlement and agriculture, while archaeologist Mats Anglert (e.g. 1995, 2003)

through the use of various quantitative methods has presented interesting new

theses on Scanian church building and parish organization. Both scholars

originate from the interdisciplinary environment at Lund University at the time

of the Ystad Project. The main caretaker of historical geography at Lund

University today is human geographer Tomas Germundsson, whom together with

Peter Schlyter have produced an Atlas of Scania (1999), a very fine

example of a modern historical-geographical atlas. The leading centre of

historical geography in Scandinavia today is, however, situated further north

in Stockholm University, where the Institute of Human Geography houses an

actual department or centre for Historical Geography and Landscape Studies.

Among the many capacities related to this centre, one could mention Mats

Widgren (e.g. 1997, 2003), Ulf Sporrong (e.g. 1998), Ulf Jansson (e.g. 1998),

Kristina Franzén (e.g. 2002), and Johan Berg (e.g. 2003). Located not far from

Stockholm, Janken Myrdal (e.g. 1985, 1991, 1999) of the University of

Agriculture in Uppsala is one of the leading scholars in agricultural history

of medieval and early modern Sweden. In recent years, a promising

interdisciplinary centre for agricultural history has been started in Uppsala

by Myrdal together with historical geographer Clas Tollin (e.g. 1999) and a

crew of talented PhD-students.

In Denmark,

the last 10 years has been characterized by a number of interdisciplinary

research projects and symposia within the area of historical geography, often

with development of the cultural landscape over time as the overall theme (e.g.

Etting 1995, Fabech & Ringtved 1999, Dalsgaard & al. 2000, Møller &

al. 2002). In this context, a special mentioning should be attributed Per Grau

Møller for his great participation in several of the projects, seminars, and

other initiatives, which for the last decennium have laid the scene for

historical geography in Denmark

Even though

historical geography neither institutionally nor as an applied term holds the

visible position, which it had in the 1970s, its basic interdisciplinary idea

is still very much alive among scholars in present-day Denmark. A promising

sign of this is a fine string of on-going or recently finished PhD-theses from

various disciplines. As examples can be pointed to the study of Danish ‘polder

history’ by geographer Morten Stenak (2005), and the work of pollen analyst

Anne Birgitte Nielsen (2003) on G.I.S.-modelled mapping of vegetational

land-cover development based on pollen analyses, while the on-going studies

include historians Adam Schacke and Peder Dam (both on manorial organization in

early modern Denmark), place-name scholar Birgit Eggert (on distribution of

Danish holt-settlements), and archaeologist Mette Busch (on medieval and

early modern landscape development in coastal areas). Thus, not only in Sweden

but in Denmark too, the future of historical geography - at least by doing, if

not by name - looks confident for at least one more generation.

2. Presentation

of the studied region : North-Western Zealand

Object of

the present series of historical-geographical analyses is the north-western part

of Zealand, which is the biggest of the Danish isles (figure 2.1). Basically,

the region has been selected because it is of a suitable size for the

analytical purpose, and it offers a cultural and physical geography which can

be regarded as representative for a great part of Eastern Denmark. Still, in

matters of historical geography, it has - until now - been a rather overlooked

region. And finally, it is my personal home region, which gives me a natural

advantage in form of a local insight that I could never achieve for other

regions in the available time given for a master’s thesis.

Figure

2.1. Overview map of NW-Zealand with boundaries of the included hundreds, and

medieval towns in- and outside the region. The inserted small map of Denmark in

the upper right corner shows the location of the analysed region.

The region

of North-Western Zealand (henceforth: ‘NW-Zealand’) is arbitrary in the sense

that it cannot claim any physical-geographical or historical identity, which

differentiates it from the adjoining parts of Zealand. For a large part it is

separated, though, from the neighbouring districts by two major streams, Tude Å

to the south and Elverdams Å to the east, together with the inlet Isefjord in

the north-east (figure 2.2). Furthermore, the region consists of six medieval

‘hundreds’ (Danish: herreder), administrative and juridical units, each

with their own local court (Danish: ting). The names of the hundreds in

NW-Zealand are Ods, Skippinge, Ars, Tuse, Løve, and Merløse, and even though the

hundred units themselves are of no importance in the performed analyses (where

the data will be analysed in geographical units of vills, parishes, and

specially defined ‘land-type areas’), their names will be used continuously

throughout the survey in order to help the reader orientate his or her way

around the regional descriptions. Also, the boundaries of the hundreds will

appear on most of the depicted maps.

My survey

of the historical geography of NW-Zealand is purely oriented on the rural

districts, where the only focus on the towns is in regard of their influence on

the rural hinterland. Indeed, NW-Zealand is primarily a rural region, as the

major historical cities of Zealand all were located in the east (the episcopal

seat and high medieval capital of Roskilde, the late medieval capital of

Copenhagen, and later on the important toll-city of Elsinore). In the

north-western region, we have three medieval towns with royal charters:

Kalundborg to the west, Holbæk to the east, and Nykøbing to the north. To the

immediate south of the region, the medieval town of Slagelse is located. While

Slagelse appears to be the oldest urban centre on Western Zealand, known as

such from the eleventh century, the oldest town within the north-western region

is Kalundborg, which grew up around the perhaps strongest high medieval

fortress of the country from the twelfth century; at first a privately owned

castle, but later to be a royal stronghold. A royal base of a more modest

nature was established in Holbæk in the thirteenth century, which soon became

the most important economical centre of the region. Youngest of the medieval

towns in NW-Zealand is Nykøbing, which did not begin to take form until the

Late Middle Ages, and still by the end of the studied period only was of

limited economical and demographical size. Probably far more important was the

episcopal castle of Dragsholm in Skippinge hundred, situated strategically on

the narrow isthmus connecting Ods hundred to the rest of Zealand. Dragsholm

Castle, dated to the early thirteenth century, was not only used as an

episcopal seat and military stronghold, it was also to be the centre of an

extensive manor, perhaps the most important of the episcopal estate on Zealand.

The major

late medieval landowner in NW-Zealand was the Bishop of Roskilde, together with

the canons of the Roskilde Chapter. Otherwise, most of the land was owned by

local magnates of only limited regional importance. In earlier times, where the

sources are scarce, various branches of the royal family and the powerful

magnates of the White family seem to have possessed a significant part of the

region, but through gifts and grants a great part of these estates came to the

Church, mainly represented by the episcopal seat in Roskilde. NW-Zealand is

unusual in the way that it has never housed a monastery. Estate wise, the

region was not without its monastic influence, though, as three major

monasteries were situated to the immediate south of the regional ‘boundary’, of

which especially the Cistercian abbey of Sorø, one of the greatest landowners

in medieval Denmark, held a lot of property in the southern and central parts

of the region. In 1536, the Lutheran king Frederik III announced the closing of

the Catholic Church in Denmark, and by doing this, all ecclesiastical estates

became royal property. Some of it was given back to the now Lutheran Church in

a more restricted way, while an other extensive part was given or exchanged to

the king’s supporters in the government, but in NW-Zealand, the majority of the

former episcopal land were allocated as entailed estates for the new royal

representatives, the lensmænd, who governed the region from the royal

castles in Kalundborg, Holbæk, and Dragsholm.

The net

spatial area (excl. medieval towns, major lakes, fiords, and areas drained in

modern times) of the analysed region is 1,664 km².

Physical geography of

NW-Zealand and identification of the land-type areas of the survey

During the

Ice Age, NW-Zealand was - as the rest of the area later known as Denmark -

overflowed by several glacial movements, and the entire region was covered by

the so-called ‘Late Baltic Iceflow’ at the end of the Weichselian Glaciation.

During the general retreat of the ice (10,000 BC), several smaller pushes forwards occurred,

which have resulted in a number of more or less distinct end-moraine lines in

the region. The most impressive of these are the ‘Bows of Ods hundred’ in the

northern part of the region, including the steep hills of Bjergene (‘The

Mountains’, no less) with the regional high point in Vejrhøj (‘Weather Hill’)

at 121 metres above sea level to the north-west of the glacial basin of

Lammefjord (figure 2.2). Otherwise, the geology of the region is characterized

by a fragmented mixture of stagnant-ice landscapes (hilly terrain with no

systematic orientation and with numerous wet hollows), moraine plains (flat or

slightly undulating landscape with loamy soils), and meltwater plains (quite

flat landscape with sandy soils).

Figure

2.2. Physical-geographical map of NW-Zealand (before the nineteenth-century

draining projects) with lakes, streams and wetland areas, as well as the most

important landscape names.

As seen on

the map in figure 2.2, the hilly terrain is prominent to the north of

Lammefjorden, north of Lake Skarresø, and in the central and eastern parts of

the region, while large coherent plains are found in the west, and south of the

fiords. South of Åmosen, a ‘highland plain’ is situated in conjunction with a

major plateau on the central Zealand. Hydrographically, the region is dominated

by the largest coherent wetland area on Zealand, Åmosen (‘The Moor along the

Stream’), which is geologically based on a glacial meltwater plain in the

south-central part of the region, with somewhat limited possibilities of

natural draining due to the surrounding terrain. The wetlands do have an outlet

through Halleby Å, the biggest stream of the region, which flows through the

lakes of Skarresø and Tissø before it reaches the sea in Great Belt. Especially

along the upper course of the stream, water has spread to the extensive meadows

of Åmosen. A smaller version of the same hydrography is found along Tuse Å with

an outlet in Holbæk Fjord south of Cape Tuse. Of general geographical interest

it could be noted that the greater part of the Lammefjord has been dammed and

drained in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which has added 55 km² of

dryland to the region; the most extensive damming and draining project in

Danish history.

Soil

conditions in NW-Zealand are, like the terrain, for a large part formed in the

latest Ice Age, where the entire region as mentioned was overflowed several

times by glaciers. Hence, the chief part of the region is covered by a moraine

bed of mixed debris material (till), which on Zealand consists of 5-25 per cent

clay, often of a quite calcareous content, which makes it well-suited for

arable agriculture. In addition, the region holds considerable areas of

meltwater sand, primarily as deposits on outwash plains, e.g. located on the

outer side of the Bows of Ods hundred, on the outer parts of capes Røsnæs and

Asnæs, and especially in the areas to the north and south of Åmosen. Of

postglacial deposits, the region is slightly marked by shifting sand along the

coastline of the Sejerø Bay and the north coast of Ods, but more importantly,

there are numerous and often quite considerable areas of freshwater deposits,

of which the most extensive are located in the region’s central part at Åmosen

and around the upper course of Tuse Å, together with several formations alongside

the major streams. In the hilly areas of terminal moraines, the soil is often

dominated by sand and gravel, while the stagnant-ice terrain with its mixture

of steep hills and ‘kettle holes’ often is characterized by moraine soils of

differing clay content.

Figure

2.3. Geological soil map (1:200,000) for the north-western and central parts of

Zealand.

The

geological soil types are, so to speak, the parent material of which the top

soils of today have been generated. In Denmark, soil-type classifications have

been performed and mapped for both the geological soils and the top soils.

While focus of the first classification is on the origin of the soil, the

latter is only concerned with the present-day textural condition of the top

layer and the content of humus. Naturally, there is a considerable connection

between the geological parent soil and the upper soil type, so that meltwater

deposits mainly have produced sandy soil types (with small spots of very clayey

soils), the moraine bed has produced loamy soil types, and the freshwater

deposits in most cases have generated a humus soil. There are, however, also

important variations. This is especially evident in the moraine bed areas,

where we find three loamy soil types. Most common in NW-Zealand is the soil

type ‘loam’ (with the type code FK4), which can be described as a medium-clayey

loam. Elsewhere, especially in the western part of Ars, the moraine bed has

generated quite extensive areas of the heavier ‘clayey loam’ (FK5), while in

other places (such as west of Åmosen, in southern Ods, and at Cape Tuse), the

top soil has developed into a lighter ‘sandy loam’ (FK3L).

In order to

be able to evaluate any influence from the physical-geographical conditions on the

human-geographical development in NW-Zealand in the period 1000-1688, the

regional-comparative analyses will be supplemented with a comparative study of

twelve specially selected ‘land-type areas’ from the region (figure 2.4 and

table 2.1). Each land-type area is characterized by a rather homogeneous

physical geography in regard of terrain and soil conditions. Still, most of the

land-type areas will contain minor sub-areas of deviating soil types, and to

prevent these from disturbing the average values of the individual land-type

areas, only data from those of the vills or parishes within the area, which do

indeed comply with the selective specification of the land-type area in

question, will be included in the average calculation (e.g. at least 66 per cent

of the area within the vill/parish should be classified as soil type FK4).

Several of the selected land-type areas have identical physical-geographical

conditions (at least according to the selective specifications), and thereby it

will be possible to test, if land-type areas within such groups behave fairly

alike, or whether for example the location within the region appears to

influence. The twelve land-type areas are selected in such a way that all the

primary terrain- and soil types in NW-Zealand (and, hence, in Eastern Denmark

as general), are represented. As seen in figure 2.4, where the land-type areas

are depicted on a background of the (top-)soil-type distribution, the districts

north of Lammefjorden are not represented at all by the land-type areas, which

is due to the fact that the terrain- and soil conditions in Ods hundred are so

alternating and fragmented that it is almost impossible to find a potential

land-type area with homogeneous conditions of sufficient size.

Figure

2.4. Map of soil types in NW-Zealand with focus on the twelve selected

land-type areas of the survey. The numbers relate to references in the text and

table 2.1. Note, that only analysed units (vills or parishes) within the area,

which do comply with the selective land-type-requirements of soil and terrain,

are included in the analyses.

Table

2.1. List and short description of the 12 selected land-type areas of

NW-Zealand.

|

Land-type area |

Physical- Terrain |

geographical characteristics Soil conditions Net area (ha) |

||

|

1 |

W-Ars |

Plain |

Moraine clay (till). At least 50% FK5. |

7,797 |

|

2 |

NW-Merløse |

Plain |

Moraine clay (till). At least 66% FK4. |

4,128 |

|

3 |

E-Merløse |

Plain |

Moraine clay (till). At least 66% FK4. |

2,745 |

|

4 |

N-Tuse |

Plain |

Moraine clay (till). At least 66% FK4. |

5,228 |

|

5 |

Skippinge |

Plain |

Moraine clay (till). At least 66% FK4. |

3,144 |

|

6 |

W-Løve |

Plain |

Moraine clay (till). At least 66% FK4. |

11,768 |

|

7 |

Cape Tuse |

Plain |

Moraine clay (till). At least 50% FK3L. |

3,881 |

|

8 |

SE-Merløse |

Hilly |

Moraine clay (till). At least 66% FK4. |

5,077 |

|

9 |

E-Løve |

Hilly |

Moraine clay (till). At least 66% FK4. |

3,352 |

|

10 |

E-Løve |

Hilly |

Moraine clay (till). At least 50% FK3L. |

1,559 |

|

11 |

Lake Skarresø |

Both plain and

hilly |

Meltwater sand. At least 50% FK3S. |

7,444 |

|

12 |

Åmosen |

Plain |

Freshwater deposits. At least 33% wetland. |

9,983 |

3. Agriculture

in seventeenth-century NW-Zealand

My analyses

begin with the traditional, retrospective starting point in Danish medieval

geography: the Land Registers of 1662 and 1688. Both land registers were

attempts of the state to come up with a fair taxation system for the entire

kingdom. The first register of 1662 was based on the rent rolls of the estates.

Annual sown acreage and rent, both divided in kinds of crops and rental

mixture, were recorded, and based on this, a taxation rate called hartkorn

was calculated for each farm. For instance, a farm paying an annual rent of 1

pound of barley, 1 pound of rye, 2 barrels and 4 bushels of oats, 1 lamb, 1

goose and 4 chickens, would, if the rent was found to correspond with the sown

acreage, be assessed to about 10 barrels of hartkorn. In 1688, this rent-based

land register was replaced by a new and quite ambitious registration, as every

single farm of the kingdom had its arable acreage (usually split up in numerous

furlongs) measured in actual size and evaluated for soil quality. Combined with

a more rough estimation (‘à l’advenant’) of the access to pastures and

meadows, a new taxation in barrels of hartkorn was carried out for each farm.

An average farm with 35 barrels of arable land (19.6 ha) of a normal soil

quality in NW-Zealand, would, for instance, be assessed to a taxation of about

7 barrels of hartkorn.

Extent of cultivation

(arable percentage 1688)

Based on

the two seventeenth-century land registers, I have tried to analyse the

contemporary perception of land value on different soil types and terrain types

in the region, together with variations in agricultural land use. First, I have

looked into the relative extent of cultivation around each village, by

comparing the sown acreage recorded in 1688 with the entire vill area (i.e.

arable land, pastures and meadows). In NW-Zealand, the average arable

percentage is found to 46 per cent, going from an average of 41 per cent in the

hundred of Merløse to 54 per cent in Skippinge. On the Danish Isles, which were

in general intensively cultivated in 1688, the arable land usually constituted

30-60 per cent of the vills. However, in many regions it is possible to find

areas of either a higher or a lower arable percentage. This is also the case in

NW-Zealand.

Figure 3.1.

Arable percentages in NW-Zealand 1688 calculated as the recorded sown acreage

as a percentage of the entire vill area. Urban lands are not included. The bold

lines represent boundaries of the medieval hundreds.

As shown in

figure 3.1, the highest arable percentages of the region can be found to the

south and north of the city of Holbæk, around the inner Lammefjord, and in the

western parts of Ars and Løve. In the central part of the region, however,

there is a huge area with relatively low arable percentages, which corresponds

nicely with the terrain map (figure 2.2), as this is an area of either hilly

terrain or widespread wetlands. Also the northern parts of Ods show a limited

cultivation; this can partly be explained by some of the poorest soils in the

region (very sandy).

By looking

at the twelve land-type areas of the survey, a rather distinct correlation

between physical geography and the extent of cultivation emerge (figure 3.2).

The primary factors of influence seem to be the subsoil (the parent deposit

material) and the terrain relief, whereas variations of texture in the top soil

show no importance. In all but one of the areas of plain moraine lands (the

seven top areas in the figure), the average arable percentages of the vills are

found to be as close as 59-61 per cent. For the sole exception, northern Tuse,

the average percentage is 50; neither the physical nor the cultural geography

offers any obvious explanation for this. In the three areas of hilly moraine

land, the average extent of cultivation is somewhat lower; 43-45 per cent on

loam, 32 per cent on sandy loam. Even if Denmark in general and the Danish

Isles in particular to the rest of the world will appear rather flat, the

terrain has proven its influence on historical geography in other studies also.

On the island of Funen, for instance, Per Grau Møller has found that in hilly

terrain, the arable percentages according to the 1688 land register were quite

low, no matter what the soil type (Møller 2000). Moving on to the sandy soils (formed

on glacial meltwater sand deposits) around Lake Skarresø, the vills in this

area show an arable percentage quite similar to vills of the hilly moraine

lands (39 per cent), whereas the wetland-dominated vills around Åmosen on

average only had cultivated 29 per cent of their land.

Figure 3.2. Average arable percentages in

twelve land-type areas of NW-Zealand in 1688.

Soil and

terrain alone, however, cannot explain all variations in the region. For example,

the coastal forelands to the west and north, and the northern side of the capes

in the Isefjord, had low arable percentages in 1688 regardless of the physical

geography. This could indicate, that a weatherly exposed position towards the sea did not inspire to an expanding

of the arable. In general, the low extent of cultivation in the coastal

forelands of NW-Zealand does not seem to be due to a remote location and hence

long transport distances to markets, as some of the less cultivated coastal areas

are actually found in the immediate neighbourhood of the cities Kalundborg and

Nykøbing. Still, the rather high arable percentages of Cape Tuse should perhaps

be seen as a result of its location close to the city of Holbæk.

Land value 1688

By comparing

individual vill areas and hartkorn taxations, it is possible to

calculate a relative expression for perceived land value as an average for the

entire vill in 1688. For instance, the vill of Søstrup (Merløse h.) has an area

of 321 barrels of land (180 ha) and it was assessed to a total of 45.2 barrels

of hartkorn in 1688. Thus, the average land-value rate of the vill is 7.1

barrels of land per barrel of hartkorn (bol/boh); the more barrels of land it

takes to equal one barrel of hartkorn, the lower was the perception of the

agricultural land value. Such an ‘area-proportional land-value rate’-method can

be criticised on several points, and for the individual vill, the method should

only be used with great caution. The potential of the method lies in the use on

a regional scale as in NW-Zealand, where all the land-value rates of the

individual vills within the region are considered as a whole (figure 3.3).

Figure

3.3. Perceived land value in NW-Zealand 1688 calculated as the entire vill area

(in barrels of land) compared to the total taxation of the vill (in barrels of

hartkorn); low land-value rates indicate a high area-proportional taxation.

Urban lands, demesnes and common pastures are not included. The bold lines

represent boundaries of the medieval hundreds.

The

land-value rates of NW-Zealand in 1688 show a rather polarized distribution.

The average rate of the region is 10.0 bol/boh, but the majority of the vills

have values of either less than 9.0 (high taxation) or more than 12.0 bol/boh

(low taxation). According to this analysis, good farm land in the year 1688

(that is with low land-value rates) was primarily widespread in the northern

and the eastern part of Merløse, in northern Tuse, and southern Skippinge, on

the south side of the two Isefjord capes in Ods, as well as in western Løve,

and south-western Ars. The poorest farm land according to the taxation was

concentrated to the central parts of the region, especially around Åmosen and

Lake Skarresø, and on the most exposed coastal forelands.

Just as the

arable percentages in NW-Zealand 1688 were found to correlate closely with the

physical geography, even more so do the vill-based area-proportional land-value

rates. Looking at the twelve land-type areas (figure 3.4), it is quite notable,

that all five areas of the medium-moraine-soil type (loam) in plain terrain

have area-proportional land-value averages inside an interval of 7.1-7.6

bol/boh. Within this interval, also the average land value of the vills on

plain clayey loam (western Ars) is situated, whereas the lighter moraine soils

(sandy loam) on Cape Tuse follow a step further down the land-value scale with

an average of 8.07 bol/boh. The next level is occupied by the two areas of

hilly loam (10-11 bol/boh), whereas the hilly sandy loam of eastern Løve on

average was valued as poorly as 14.66 bol/boh. Thus, both in plain and hilly

terrain, sandy loam was apparently considered less valuable as loam or clayey

loam in 1688; this difference is most evident in hilly terrain. Indeed, the

hilly sandy loam of NW-Zealand was on average valued as bad as the pure sand

soils around Lake Skarresø (14.78 bol/boh). At the bottom of the scale was -

once again - the group of vills around Åmosen, with an average land-value rate

as low as 17.26 bol/boh.

Figure

3.4. Average land-value rates in twelve land-type areas of NW-Zealand 1688. The

land value is expressed by an area-proportional rate of barrels of land per

barrels of hartkorn (bol/boh). Note, that the actual land value (taxation per

land unit) grows with falling land-value rate.

To sum up,

the conclusion from this analysis is that the perceived land value in

NW-Zealand 1688 differed significantly among moraine soils, sand soils and

wetland soils, as it took two barrels of sand-soil land to equal the economical

value of one barrel of moraine-soil land, whereas the wetland wills of Åmosen

had to come up with almost 2.3 barrels of land to match a barrel of moraine

land. On the moraine soils, the terrain played an important influence on the

relative land value, as moraine soil in hilly terrain was valued at c.70

per cent (loam) or 55 per cent (sandy loam) of similar soils in plain terrain.

A

comparison of figures 3.1 and 3.3 will show a similarity, which should not

surprise. Vills blessed with high-valued soils suited for cultivation were of

course more likely than others to claim a large portion of the vill area for

arable use - and vice versa. Alternatively, the appraisers have generally

assessed well-cultivated vills higher than they did the less-cultivated vills.

Among Danish agricultural-historical scholars, it is the general opinion, that

the Land Register of 1688 did in fact systematically underestimate

non-cultivated land compared to its actual economical potential, and hence, vills

primarily orientated on arable farming were unequally heavily taxed. This claim

will be tested later in the chapter. Until then, a closer look at figures 3.1

and 3.3 will show, that the distribution patterns are not completely identical.

For instance, the first analysis found almost the same arable percentages in

all areas on moraine soil in plain terrain, but the light sandy-loam soil of

Cape Tuse was valued distinctly lower than the others. One could say that the

farmers of Cape Tuse had cultivated the same relative amount of their vill land

as farmers on heavier moraine soils had, but apparently, the sandy-loam soil

did not yield quite the same per area unit. The same can be argued even more

for the sandy soils of the region, which in 1688 were not cultivated

considerably less than were the hilly moraine soils, but still they were

clearly considered less productive according to the land evaluation.

Similar

studies have recently been performed on a national scale by Peder Dam (2004), who

were able to find average land-value rates on the Danish Isles in the area of

10.6-11.1 bol/boh, which differed distinctly from the Jutland peninsula, where

the rates went from about 15 bol/boh in the most fertile regions to 50 bol/boh

in the West-Jutland moor areas. Indeed, the national differences in land values

correlate nicely with the geological division of Denmark in the

moraine-dominated isles in the east and the sandy soils of Jutland in the west.

However, Dam also found, that vills of identical soil types generally were

taxed significantly harder (and so valued higher) on the Isles than they were

in Jutland. Especially, the Zealand sand soils were rated remarkably high,

which were particularly evident in Eastern Zealand near the major cities. In

fact, on Zealand as a whole it was Dam’s conclusion, that terrain was more

influential on land-value rates than was the soil.

In England,

Bruce Campbell (2000) has used a related area-proportional method to establish

arable land value on fourteenth-century demesnes. His study would indicate,

that medieval land value on English demesnes was by large a product of three

factors: land-productivity value, access to manpower, and distance to (or

accessibility of) urban markets. Something similar is quite possible for

NW-Zealand, as there is a tendency of increasing arable percentages and land

value in the immediate neighbourhoods of the cities of Holbæk and Kalundborg,

and Dragsholm Castle, which cannot be explained by physical-geographical

conditions only. However, such relations have not been tested systematically in

the present analyses.

Crop mix 1662

The three major species of grain on

seventeenth-century Zealand were barley, rye and oats. In some districts, also

buckwheat and dredge (a mixture of barley and oats) held some importance. Wheat

had lost its position as primary bread grain in Scandinavian agriculture during

an unfavourable change of climate during the Iron Age, and still by the

seventeenth century, it did not appear in NW-Zealand rent rolls. Based upon the

information of the 1662-Land Register, it is possible to calculate the relative

crop-mix combination on the sown acreage of each farm. In figure 3.5-3.7, these

numbers have been summed up to parish level to give a clearer picture of the

intra-regional tendencies.

Barley was

the primary grain of the region at this time, as it was for most of the nation.

Not only was it used for malt and producing beer, it was also an important food

grain for both porridge and bread; since the Viking Age, it had been the

primary substitution for wheat. Thus, barley was grown in every parish of the

region (and with few exceptions in every vill), and to judge from accounts of

seed and rent, normally around half of the annually sown acreage was used for

barley; in most parishes, the barley share lies within 40 to 60 per cent

(figure 3.5).

Figure

3.5-3.6. Average percentages of sown acreage used for barley (3.5) and rye

(3.6) in the rural parishes of NW-Zealand according to seed and rent data in

the Land Register of 1662. The bold lines represent boundaries of the medieval

hundreds.

Since

almost all arable land on seventeenth-century Zealand to some extent was used

for barley, it is perhaps more interesting to look at the distribution of the

other main crops. The second most important crop was rye, which gained ground

during the Middle Ages as a better bread grain than barley. Even today, rye

bread is a basic part of Danish cuisine. As shown in figure 3.6, the

1662-distribution of rye in NW-Zealand is far more systematic than it is for

barley. In the eastern Ars, rye actually covered almost half of the sown

acreage. On a regional basis, rye constituted around 20 per cent of crop

production, and hence also the parishes around Åmosen, in Tuse, and

south-western Løve manifest themselves as rye-cultivators above average. Large

areas of limited rye-growing can be found in Merløse and especially in Ods.

The part of

the arable land in NW-Zealand, which in 1662 was used for neither barley nor

rye, was primarily used for oats. Besides oats, buckwheat and dredge were grown

with varying weight around the region. All these secondary crops are known to

have been used for human food, but their main function on seventeenth-century

Zealand were as fodder, especially for horses. The average percentages of

arable land sown with secondary crops are shown in figure 3.7. There are some

variations in the type of fodder crops used in different parts of the region.

Oats had its main importance in eastern Løve, western Ars, and south-eastern Merløse.

In Ods, eastern Ars, Tuse, and western Merløse, growing of buckwheat is

recorded, while dredge primarily was grown in the hundreds of Ods and

Skippinge.

Figure

3.7. Average percentages of sown acreage used for secondary crops (oats,

buckwheat and dredge) in the rural parishes of NW-Zealand according to seed and

rent data in the Land Register of 1662. The bold lines represent boundaries of

the medieval hundreds.

Crop-mix

percentages for the 12 land-type areas of the region are calculated in figure

3.8. In the vills on the plain moraine soils, usually around half the arable

acreage was sown with barley. In the areas of hilly moraine, the percentage of

barley was generally higher than it was for parishes on the plain moraine

(around 60 per cent). The barley percentages should for a large part be read in

coherence with the alternatives. This will show that variations in barley

percentages are followed by almost similar counter-variations in rye

percentages. In most areas with plain moraine soil, 20 to 25 per cent of the

arable land was used for rye, while in the hilly moraine areas, rye average was

down to around 11 per cent.

While the

fluctuations of barley and rye almost counterbalanced each other, the average

relative share of arable land used for secondary crops kept surprisingly stable

(26 to 31 per cent) in almost every area of moraine soil, no matter what the

specific texture type or terrain. The main exception is found in Løve, where

the barley-dominated western part only had a 22 per cent share of the arable

used for oats, while the sandy loam soils in the hilly land of south-eastern

Løve saw an oats percentage of no less than 35. Most likely, farmers of the

Løve ‘highland’ have sold a fair part of their oats production to the

barley-growing farmers down on the plains.

Figure

3.8. Relative crop-mix distribution of the sown acreage in twelve land-type

areas of NW-Zealand in 1662.

The major

rye-producing district of NW-Zealand in 1662 is located in the big sand-soil-dominated

area around Lake Skarresø (eastern Ars and south-western Tuse). Here, we find

an average rye percentage of 43 per cent, accompanied by the lowest barley

percentage of all the analysed areas (38 per cent). This is in good accordance

with agricultural theory, as barley historically performs its lowest yields on

sandy soils because of its high dependence of steady water supply, which is

often a problem on the easily-dried-out sand. At the same time, Danish rye is

known to give some of its best yields on the loamy sand soils of Eastern

Denmark. A perhaps more surprising observation is that also the vills around

Åmosen apparently grew quite a lot of rye (28 per cent), which has, however,

hardly taken place on the humid wetland soils, where rye performs very poorly.

The reason for the high percentage should more likely be searched in the large

sandy areas in the outskirts of the Åmosen wetlands. In fact, too much soil

water has been the major problem in Danish rye production before modern

draining techniques were implemented in the nineteenth century. When rye on

Zealand also was grown in rather large proportions on the loamy moraine soils,

it was according to several contemporary texts more out of necessity than out

of profitability; often the yields were deplorably low, but rental obligations

and the need for bread made rye an imperative part of the crop mix none the

less. This could perhaps be part of the reason that sandy soils on Zealand in

1688 were valued significantly higher than identical soils in the generally

sandy Jutland. Based on these considerations, it is a bit more difficult to

explain the low rye percentages in the region’s three areas of hilly moraine

land. The sloping terrain should in fact be expected to improve rye yields on

moraine soils due to the natural drainage, but evidently that was not the case.

The high barley-percentages in the two hilly loam areas indicate that the

ground cannot have been all that unsuited for grain in general, as secondary

crops would then be expected to cover a larger part of the sown acreage. A

possible explanation could be that moraine soils in hilly terrain often tend to

be more saturated with water than in plain terrain, partly because of dips

without outlets, partly due to an observed tendency of moraine to generate more

compact soils on high grounds in hilly terrain for reasons still not completely

clarified.

Several

foreign studies have suggested that crop mix of the past besides physical geography

was highly influenced by market-geographical conditions. While the population

in the big cities (of which Denmark only held one in this age, namely

Copenhagen) lead to a huge demand for bread grain (which for the common people

of Denmark meant rye), malt barley often became a profitable crop in the

immediate neighbourhood of medium-sized towns and export harbours. Such urban

and market-economical influences on rural production have not (yet) been

analysed systematically in NW-Zealand, but as a preliminary support for such a

connection it can pointed out that as shown in figure 3.5, four of the parishes

closest to the town of Holbæk (northern Merløse h.), and the two parishes to

the immediate east of Kalundborg (north-western Ars h.), did in fact save a

considerable part of their sown acreage (60-70 per cent) for barley.

Seed density 1662-1688

By

comparing the annual amount of seed recorded for each village in 1662 to the

sown acreage measured in 1688 (adjusted for the fallow within the two- or three-field-system),

it should, at least in theory, be possible to calculate the average seed

density used in each vill. Now of course, there is a methodical problem in

using data from two different land registers with an internal time gap of about

20 years (the actual measuring of the arable fields on Zealand for the

1688-Land Register took place in 1682). However, as it is not very likely that

the size of the arable land has changed significantly in this exact period, the

time difference is probably the least of the problems in the proposed analysis.

Earlier attempts to analyse the 1662-seed data have shown uncertainties as to

what the data actually represent, and several studies from NW-Europe have

established quite significant variations in seed density even on a regional

scale. Not only type of crops and soil conditions, but also local customs seem

to be of huge importance. Still, nothing ventured, nothing won, and so an

attempt to calculate seed densities for the acreages of NW-Zealand villages and

demesnes in 1662-88 has been performed (figure 3.9).

Figure

3.9. Seed density in NW-Zealand 1662-88 calculated as the recorded amount of

seed (in barrels of seed 1662) compared to the measured annual sown acreage (in

barrels of land 1688). Urban lands, vills with no seed data and permanent

pastures are not included. The bold lines represent boundaries of the medieval

hundreds.

On average,

farmers in NW-Zealand used 0.39 barrels of seed per barrel of land (bos/bol) in

1662-88. For most village vills, the seed densities lies within an interval of

0.20-0.70 bos/bol; there is a distinct tendency in the region that seed density

is higher than average on demesne acreages than it is on village acreages. The

rate level itself is somewhat surprising, as the term ‘one barrel of land’ in

the 1680s actually was defined as the average area sown by one barrel of seed

on Zealand at that time. Therefore, one would expect a level closer to 1.00

bos/bol. Identical analyses from the islands of Funen and Falster, however,

have shown seed densities of similar levels (Pedersen 1907-08, Frandsen 1983).

Here, the suggested explanations have been, that either the amount of seed

listed in 1662 was ancient figures from the late sixteenth century, or the

amount of seed used in 1662 was abnormally low due to an agricultural crisis

derived from war and Swedish occupation in 1657-60. Variations within the

interval could also reflect intra-regional differences in crop mix. In Scania,

both contemporary texts and later studies show, that rye was sown less dense

than barley and oats; especially oats was sown quite dense as to prevent weeds

from gaining too much ground (Dahl 1942). Similar tendencies of lower seed

densities in areas dominated by cultivation of rye have been found on Funen

(Frandsen 1983).

A

comparison of the seventeenth-century seed densities in NW-Zealand (figure 3.9)

with the distribution of land-value rates in 1688 (figure 3.3) will show that

there is a clear tendency towards higher seed densities on the better valued

lands. A link to soil quality also appears, when looking at the twelve

land-type areas (figure 3.10), but only between the main soil groups of

wetland, sand and moraine. Within the moraine-soil groups, the averages seem to

point in all directions.

Figure 3.10. Average seed densities in twelve

land-type areas of NW-Zealand in 1662-88.

By second

look, there is, however, a quite distinct pattern also on the moraine soils of

the region regarding seventeenth-century seed density: The densities are

generally higher in the western areas than in the eastern - no matter what the

soil type and terrain type, and even on equally well-valued land. No obvious

explanation for this uneven distribution springs to mind. Surely, the sandy

rye-dominated land around Lake Skarresø does have a seed density in the low end

of the scale (0.29 bos/bol), and so it could support the findings from Funen

and Scania of a low seed density for rye, but it is no lower than the densities

found in the barley- and oats-dominated areas of Merløse (0.27-0.32 bos/bol).

The perhaps strongest indication for a relation between crop mix and seed

density is found in the hilly areas of eastern Løve, where oats could be part

of the reason for the quite high densities. Could it then be that farming

traditions altered so much between east and west within this relatively small

region?

Being

partly based in physical geography, I would, however, like to find a more

physical and measurable factor of explanation, and such a factor does indeed

emerge, when looking more closely at the soil map. Being quite alike on

soil-type distribution in general, the predominantly loamy soils of Merløse

are, as shown in figure 3.11 (right), covered with numerous tiny green dots,

indicating the presence of small spots of wetland scattered all over the area -

in hilly terrain as well as in plain. Similar green dots can also be found in

the western hundred of Løve (figure 3.11 left), but in far smaller numbers.

Supplementary analyses confirm a general tendency in the entire region towards

lower seed densities in areas with a high proportion of small wetland spots;

the soil map records such spots down to a size of approximately 50 m², but it

is most likely that several even smaller spots have existed in real life in the

same areas - in the seventeenth century, that is, as field draining has cleared

off most of them today. The reason for this difference is geo-morphological.

For some reason, the plain moraine landscape of Merløse is a bit more ‘bumpy’

or undulating than the plains of the west, and together with the thick moraine

beds below the top soil, water apparently tend to ‘get caught’ for longer

periods in many of these ‘moraine-terrain troughs’. The findings correlate with

studies from Funen, which show that in some vills only two thirds of the annual

sown acreage were actually sown in the 1680s, the rest being left for grazing

because of pure soil quality due to water, stones, clay, sand, etc.

(Porsmose 1991). It is interesting, though, that this rather distinct physical-geographical

difference between the eastern and western land-type areas of NW-Zealand only

emerges when looking at seed density, and not at all appears when looking at

arable percentages or land value.

Figure

3.11. Soil maps of the main parts of Løve hundred (left) and Merløse hundred

(right). Brown colours show loamy soils, orange colours sandy soils,

light-green colour wetland soils; the dark-green colour indicates areas with no

record of soil type (mainly cities or forests). The black lines represent

boundaries of the medieval hundreds.

Production mix (arable

versus pastural) 1662

As claimed

in the opening analysis, the percentage of the vill area used for arable land

can be seen as an indicator of orientation in the rural production on arable

and/or pastural production. Another and more direct approach to analyse

production-mix variations is based on the Land Register of 1662. In this

register, the actual rent for each village farm and its distribution on the

different kinds of payment is documented. In some villages, mainly where all

village farms were owned by the same landlord, the farms could be equalized to

exactly the same size with the exact same rent. An example of this from the

region is the village of Butterup (Butterup parish, Merløse h.), where all 12

farms were owned by the neighbouring manor, all of them had an arable acreage

rated to take 4 barrels of seed, and all of them paid a rent of 16 bushels of

barley, 15 bushels of rye, 3 bushels of oats, 1 lamb, and 2 chickens. In most villages

of NW-Zealand, the picture was, however, more alternating. For some villages it

is even possible to find that while one farm was to pay practically all its

rent in grain (barley and rye), another farm in the same village mainly paid

its rent with butter or fodder. Such differences are usually related to

manorial ownership, as different manors could have different preferences for

mix of payment. Also, variations in manorial ownership could lead to different

levels of rent in the same village. The most common finding is, however, that

the farms of the individual village had a reasonable similar correlation

between rent and amount of seed (i.e. arable land), as well as a quite

homogeneous rent-payment mix. Therefore, the total rent of the village does give

a good indication of the conditions for the individual farms, and as the

average village rent-mixes also paint a rather systematic picture on the

regional scale, it seems fair to presume, that the rent-mix-distribution to a

large extent also represents the actual production. It should be emphasized,

though, that the actual percentages of various kinds in the tenancy payments

are not claimed to equal the actual percentages in the production mix. A grain

percentage of 75, for instance, does not mean that exactly 75 per cent of the

gross production value came from grain. The figures should only be used as

relative indicators of the orientation in the rural production.

In 1662,

the average tenant in NW-Zealand paid 81 per cent of his rent in grain (43 per

cent barley, 15 per cent rye, and 23 per cent oats). The remaining 19 per cent