Scriptores ordinis predicatorum

de provincia Dacie online

Fr. Augustinus de Dacia OP and his Rotulus pugillaris

Transcribed,

edited and translated by Christian Troelsgård,

University of Copenhagen, 2021.

Introduction by J.G.G. Jakobsen, Centre for Dominican Studies of Dacia, 2021.

Introduction

The most prominent Dacian contribution to

Dominican theological literature was authored by Fr. Augustinus

de Dacia (†1285), who was prior provincial of Dacia in the periods 1261-1266

and 1272-1285. Nothing

is known about him before his first election as provincial in 1261,

but he most likely originated from one of the Danish convents. He was absolved

from the provincial office for unknown reasons by the General Chapter in 1266,

but was nevertheless still referred to as prior provincial, when excommunicated

by Cardinal Legate Guido in 1267

along with other ecclesiastical supporters of King Erik V Glipping

against the fugitive Archbishop Jakob Erlandsen of Lund. Fr. Augustinus

was reinstalled as provincial in 1272

and this time remained in office until his death in 1285. As prior provincial, he was enjoined

to administer the Scandinavian collection of papal taxes and monetary aid for

the crusade to the Holy Land, and to personally engage in the preaching of the

Cross for the Holy Land, just as he was papally commissioned to act as judge in

a dispute between Bishop Tyge of Århus

and the Cistercian Abbey of Øm in 1264.

Furthermore, he took part in a diplomatic meeting between the three

Scandinavian kings in Horsaberg in 1276.

Provincial Augustinus is mentioned in several of the

letters by Fr. Petrus de Dacia, and must have shared

the positive attitude of Petrus towards Dominican

pastoral care of religious women, as it was during his offices that the

province saw the foundation of the first two Dominican nunneries in Roskilde (1263-64)

and Skänninge (1281).[2]

At

some point in his career, Fr. Augustinus de Dacia

wrote the Rotulus pugillaris,

of which the title can be translated as ‘the tiny handbook’. It is probably a

short version of Augustinus’ own Compendiosum breviarium theologicae,[3] to which he refers in the Rotulus, but

whereas the handbook version has survived in two extant manuscripts, the more

extensive work is long lost.[4]

Still, the handbook version of the Rotulus was without doubt also the most read and influential

of the two, used as a practical tool for the friars’ studies and preparation

for the task of preaching. The Rotulus can be

described as a short manual for beginners in the study of theology, offering a

condensed presentation of all useful and necessary theological knowledge that a

friar needed to acquire before being allowed by his prior to preach. In the

prologue, Fr. Augustinus emphasizes the importance of

a firm handling of pastoral knowledge. The friars should know the fundamental

definitions and concepts of Christian faith in order to describe and legitimate

good behaviour. He also had to learn the doctrine of virtues and vices, the Ten

Commandments and sins, the Sacraments and means of grace. Furthermore, he was

expected to cope with Christian dogmata and thus be able to explain and anchor

particular rules within a Christian worldview.

The text consists of 15 chapters each

treating a theological topic, mainly by defining it without any further

discussion. The topics include: the science of theology, the Creed and the

articles of faith, angels and souls, grace, theological virtues, the gifts and

works of compassion, blessedness and contemplation, prayers, plagues, vows,

sins in general and specific sins, Sacraments, distinction of times, and

Antichrist and the Final Judgement. Almost all topics are presented in either

three, four or twelve categories, regularly concluded by one, two or three

mnemonic verse(s) in the form of intended hexameters and/or disticha

at the end to sum up the main teaching of each section. An example is a verse,

which became widely popular in the Middle Ages, used

to summarize the four ways of scriptural exegesis: “Littera gesta docet, quid credas allegoria. Moralis quid agas, quid speres anagogia.”[5] Indeed, this was perhaps one of the most

important practical methods that the young Dominican friar was taught by the Rotulus, that is to expound the Holy Scripture according to the

system of the four senses. By adopting the exegetical technique of the

universities, the friar was enabled to break down the knowledge of the Bible

into an easier accessible form for his lay audience.[6]

The teaching of Rotulus is based on a number of classical texts, including the inevitable

church fathers Augustine, Gregory the Great, Peter Lombard and Gratian. Fr. Augustinus also includes Aristotle, from whose work De anima he draws the essential

knowledge about soul and wisdom. Of mendicant scholars Augustinus

only refers explicitly to Fr. Raymundus de Peñaforte OP, but his work also shows similarities with Fr.

Albertus Magnus OP and Fr. Bonaventura OFM (Breviloquium),

and echoes – directly or indirectly – a familiar and contemporary manual in

theology by Fr. Simon de Hinton OP, the prior provincial of Anglia (1254-1261).[7]

More surprisingly, however, it is difficult to point to any direct influence

from Fr. Thomas Aquinas OP, which may indicate that the Rotulus was written early within Augustinus’ career, before the teachings of Aquinas really

broke through.[8]

Fr. Augustinus

de Dacia’s Rotulus pugillaris was

apparently meant for the education of young Friars Preachers in his own

province. We know that a copy existed at the Dominican convent in Helsingborg,

as one of the two extant versions according to an inscription belonged to Fr. Nicolaus Lagonis from this house;[9] most likely he is identical to a lector of that same name

known in the convent in the 1370s.

It has even been suggested that certain elements in it reflect the ongoing

missionary work in Estonia, which may be expressed in the description of the

Friars Preachers as fidei pugiles and

in a slight variation in the focus of the two extant versions on moral theology

in the one and apologetics in the other.[10] This educational text book

from Dacia may, however, also have played a role in the Order’s teaching

elsewhere in Europe, especially in the German provinces, where the title

appears in several library lists, while the only other extant copy is found at

the University Library of Basel.[11] A final indication of an international recognition of Fr. Augustinus’ Rotulus is given in the fact that it is included in a late

medieval list of the most important authors and works of the Dominican Order.[12]

The Rotulus pugillaris by Fr. Augustinus

de Dacia is extant in two manuscripts, both in the form of transcripts from

around 1400 as part of compilations of mainly Dominican works: one is preserved

in the Uppsala University Library (Ms. C 647, fol. 159v-176v), the other in Universitätsbibliothek Basel (Ms.

B X 9, fol. 37r-69r). It has been edited and published twice by Fr. Angelus

Maria Walz OP: first as ‘Fratris

Augustini de Dacia O.P. »Rotulus pugillaris« examinatus atque editus’ in two volumes of the Dominican journal Angelicum vol. 5,

pp. 380-406, and vol. 6, pp. 253-278 and 548-574, Rome 1928-29; secondly in Classica et Mediaevalia -

Revue danoise de philologie

et d’histoire vol. 16, pp. 136-195, Copenhagen

1955.

The

present new digital edition is based on both manuscripts and transcribed by

Christian Troelsgård, University of Copenhagen, with

some corrections compared to the latest edition by Walz

noted in the introduction. The most important of these concerns the overall

title of the full (lost) original work and that

‘anger’ is re-introduced as one of the seven capital sins defined by Saint

Augustine. Below are links to a full transcript of the Latin text with an

introduction in English, as well as a version with a parallel translation in

Danish

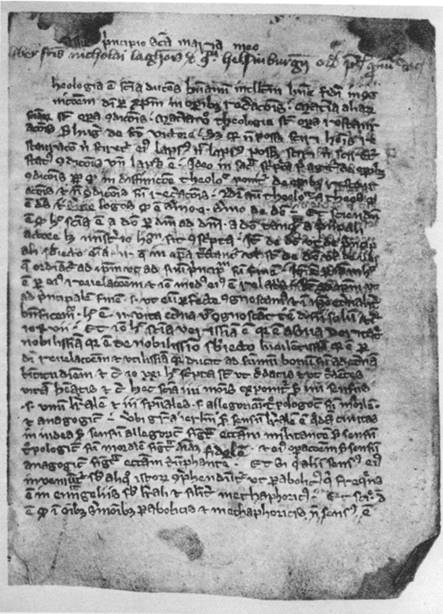

Left:

Ms. C 647, Uppsala University Library, which contains one of the two extant

medieval transcripts of the Rotulus pugillaris.

Right: The first page of the Rotulus pugillaris in C 647.

Notes for the introduction

[1] No known image of Fr. Augustinus de

Dacia is preserved. This picture of a blessed Friar Preacher holding a book,

while sitting on a devil, is a detail from an altarpiece in the former

Dominican church of Our Lady in Århus, Denmark, supposedly made by the Danish

master artisan Claus Berg around 1530. The friar is not straightforwardly

identified. The most commonly made identification is with St. Dominic himself.

One alternative suggestion (Halvorsen 2002, pp.

14-15) is, however, that he represents Fr. Albertus

Magnus (c.1193-1280),

a leading academical capacity of the Dominican Order

teaching at the Order’s Studium generale in

Cologne since 1248, and thus a likely contemporary teacher and role model for

Fr. Augustinus.

[2] For the full biography of Fr. Augustinus

de Dacia, see DOPD 1261

(20/4).

[3] Earlier referred to as Compendiosum Breviarium Theologiae, as in Walz’ editions and the dependent literature. However, the

only manuscript that brings the prologue, B = Basel, Universitätsbibliothek

B X 9 (c. 1400), reads clearly theologice, sc. theologicae

<scientiae>, a reading corroborated by the rubric of the first of the

fifteen chapters.

[4] The Compendiosum Breviarium Theologicae is in turn characterised as a summula (diminutive), probably in order to

distinguish it from major works as e.g. Fr. Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae.

[5] “The literal reading teaches what happened, the allegorical what

you ought to believe, the moral what you should do, and the anagogical what you

should hope for.” In recent years, Fr. Augustinus’

couplet has received extra attention as it was cited twice by Pope Benedict XVI

in 2008 and 2010. Harrington 2018, pp. 50-51.

[6] Walz 1955, pp. 136-137; Jensen 2012; Schütz 2014, p. 219. Fr. Augustinus

announces in the prologue: “simplicibus <sc. verbis>ad sciendum in unum quasi ‘Rotulum pugillarem’ breuiter collecta redegi” (“.. these matters I have compressed

in short form and with simple words for the sake of understanding into this -

so to speak -‘Tiny handbook”’).

[7] Boyle

1978, p. 254; Mulchahey 1998, pp. 206-207. Although both being written at about the same time by priors

provincial on similar overall topics and with a similar audience in mind, and

both citing from Raymundus and Albertus,

the structures of the works by Fr. Augustinus and Fr.

Simon de Hinton are, in fact, quite different. Troelsgård (forthcoming).

[8] Lindroth

1975, p. 72; Mulchahey 1998, pp. 206-207; Jensen

2012.

[9] “Liber fratris

Nicholai Laghonis de conventu Helsingburgensi ordinis predicatorum provincie Dacie.” Uppsala University Library, Ms. C 647, fol. 159r.

[10] “Ob wir darin einen Niederschlag

entsprechender Missionserfarungen

in Estland sehen dürfen?” Senner 2001, p. 36.

[11] In addition to the two extant manuscripts, Christian Troelsgård has found three medieval manuscripts with

quotations from Rotulus pugillaris

via the ‘Manuscripta Mediaevalia’-database.

Troelsgård

(in email correspondence, 2021).

[12] The list is compiled by an anonymous friar around 1320 and later

continued by the French Dominican Fr. Laurentius Pignon (†1449). It contains the names of seven Scandinavian

friars, among them Augustinus de Dacia: “Frater Augustinus, provincialis Dacie, scripsit libellum pro informatione

predicantium, quem pugillarem rotulum nuncupavit.” Schück 1892, p. 161.

Literature

Boyle OP, Leonard E. (1978): ‘Notes on

the education of the fratres communes in the Dominican Order in the

thirteenth century’, in: Xenia medii aevi historiam

illustrantia oblata Thomae Kaepelli O.P. vol. 1, ed. R. Creytens & P. Künzle, Rome, pp. 249-267.

Châtillon, François (1964): ‘Vocabulaire

et prosodie du distique attribué a Augustin de Dacia sur les quatre sens de

l’Écriture’, in: L’Homme devant Dieu -

Mélanges offerts au Pére Henri de Lubac, Paris, pp. 17-28.

Halvorsen OP, Per Bjørn

(2002): Dominikus - En europeers

liv på 1200-tallet,

Oslo.

Harrington OP, Jay (2017): ‘Augustine of

Dacia, O.P. (†1285) and the fourfold sense of sacred

scripture’, in: Christian Faith and the

Power of Thinking - A collection of essays, marking the 800th

anniversary of the foundation of the Order of Preachers in 1216, ed. J.

Harrington, Chicago, 35-66.

Jensen, Kurt Villads (2012): ‘Augustinus de

Dacia’, on the website: Medieval Nordic

literature in Latin - A website of authors and anonymous works c. 1100-1530,

ed. L.B. Mortensen & al. <https://wikihost.uib.no/medieval/index.php/Augustinus_de_Dacia>

Lindroth, Sten (1975): Svensk lärdomshistoria vol. 1 (‘Medeltiden – Reformationstiden’),

Stockholm.

Mulchahey, Michèle (1998): »First the bow is bent in study…« -

Dominican education before 1350, Toronto; esp. pp. 204-207.

Schück, Henrik (1892): ‘Svenska

Medeltidsförfattare (1)’, in: Samlaren

vol. 12 (1891), pp. 154-170.

Schütz, Johannes (2014): Hüter der Wirklichkeit - Der Dominikanerorden in der mittelalterlichen Gesellschaft Skandinaviens, Göttingen.

Senner OP, Walter (2001): ‘Die Studienorganisation

des Dominikanerordens im Mittelalter mit Berücksichtigung Estlands’, in: Estnische Kirchengechichte im vorigen Jahrtausend,

ed. R. Altnurme, Kiel, pp. 26-43.

Troelsgård, Christian (forthcoming): ‘Mnemonic verse, theology, and

pedagogy in Augustinus de Dacia’s (†1285) Rotulus pugillaris’, in: Dominican Culture,

Dominican Theology (‘Archa Verbi.

Subsidia’),

ed. J. Slotemaker, F. Wöller

& U. Zahnd, Münster.

Walz OP, Angelus Maria (1945): ‘Der »Rotulus pugillaris« des Aage von Dänemark

(†1285) im Licht dominikanischer Theologiepflege’, in: Antonianum vol. 20, 369-400.

Walz OP, Angelus Maria (1954): ‘Des Aage von Dänemark »Rotulus Pugillaris« im Lichte der alten dominikanischen Konventstheologie’,

in: Classica et Mediaevalia -

Revue danoise de philologie

et d’histoire vol. 15 (1954), pp. 198–252.

Walz OP, Angelus Maria (1955): ‘Des Aage

von Dänemark »Rotulus pugillaris«’, in: Classica et Mediaevalia -

Revue danoise de philologie

et d’histoire vol. 16 (1955), pp. 135-194.

Centre for Mendicant

Studies of Dacia

Postal

address: Emil Holms Kanal 2, 2300 Copenhagen S,

Denmark. Email: jggj@hum.ku.dk